As the winter arrived, few members of the Masaryk University Department of Art History accompanied by some exchange students, took off on

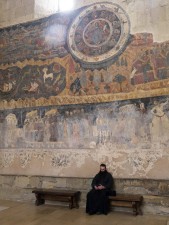

After a restful and digestive night, we set off for the journey’s first monument: the Monastery of Gelati. Situated a few kilometres from Kutaisi, it is located on a mountainside and overlooks the town. The construction of the monastery dates back to the beginning of the twelfth century, at the request of King David IV of Georgia (also known as King David the Builder), whose tombstone can be found on the ground in one of the portals leading to the monastery. Gelati was the cultural and artistic centre for centuries: the monks were known for the production of manuscripts as well as glass and cloisonné enamels. Also, the monastery has long possessed the Khakhuli triptych, a symbol of pride to the Georgian medieval heritage. The monastic complex has two churches: the Church of Nativity of Virgin Mary and the Church of Saint George. The access of the first one is made by the intermittent use of a gawit or zhamatun, which has preserved part of its original decoration: the representation of seven ecumenical councils. Probably one of the oldest versions of this iconography, these representations place particular emphasis on the imperial figure – the monastery's patron, King David IV, who personally initiated two of these gatherings. When we entered the main church, everyone stood in silence. On the one hand, out of respect for the religious service that was in progress at that time, but also – and probably above all – we were all speechless thanks the magnificence of the spectacle unfolding before our eyes. The imposing mosaic of the Madonna Nicopeia surrounded by two archangels that occupies the apsidal conch took on a whole new dimension. As if emerging from the brown of essences, the figures appeared both surreal and alive when combined with the melody of the songs, the smell and fog from the incense, and the discreet dance made from the light of the candles. It was still under the emotion of such an outstanding experience that we went to the Monastery of Saint George in Ubisi. The main church is considerably smaller in size than the one in Gelati, but the quality of the frescoes in the church of the Monastery of St George are on par, or even exceeding those of Gelati. Although the ones depicting the life of St. George on the side walls of the single nave are in poor condition, mainly due to humidity and a lack of restoration works, those on the ceiling and the apsidal part are still perfectly visible.

We settled for the night in Gori, birthplace of Josef Stalin. While taking a walk into Stalin Park (where stand both the museum and statues dedicated to the Soviet politician), we took some time to reflect on the notion of cultural heritage and its preservation. That day, we had seen two buildings which quality and attention to maintenance were drastically different, and still incomparable to the care given to the Stalin memorial. So, we went to sleep with this very question in mind. For what reasons, how, and who designate artistic and architectural monuments or personalities as regional or even national symbols?

Two days later, we discovered a new land: Armenia. We began our journey by virtually travelling back to the seventh century, and we started it in the small

village of Aruč with its church. The cathedral of Aruč,

Our discovery of the Armenian seventh century continued with a visit to another building, located a few kilometres from Aruč, probably too sponsored

by a member of an Armenian noble family: the cathedral of Talin. Like Aruč, the building is very badly preserved and is still only partially standing.

Once again, the dome has collapsed. However, it was the occasion for us to discover a new architectural form: an oblong building with an inscribed cross,

and unlike Aruč, the dome did not rest on massive engaged pillars but on four

The next day we jumped through time to the thirteenth century and visited two monasteries, both commissioned by the Prince Vache Vachutyan: Hovhannavank and Sagmosavank. These two majestic monuments are as close geographically – some five kilometres apart, as they are chronologically – built in 1215 and between 1216 and 1221 respectively. Both are situated at the top of the Kasagh river gorges, thus regaining the idea of sacralising the landscape.

Later that day, we went to another monastery, famously known for being directly carved into the rock of the mountain, the one of Geghard. While some myths date back the creation of the monastery as far as the fourth century, we know for sure that the main church was built in 1215 by the two famous brother Zakare and Ivane Zakarians, who were generals for the Georgian Queen and are acknowledged for taking back most of Armenia from the Turks. The monument is nonetheless outstanding. While entering the gawit, we suddenly discover a series of annexed rooms and chambers, most of them directly cut out from the rock. In this dark labyrinth where little light seemed to manage to squeeze through, we marvelled at the sublimely sculpted decors and the elaborate acoustics of these places.

As a conclusion, a general remark seems to be in order. The discovery, or rediscovery for some members of the group, of some of these

Cassandre Lejosne