Roads. Its anniversary provides an opportunity to look back to how the narrative constructed around Romanesque art in Iberia, the Way to Santiago, and the impact of the Islamic frontier developed and changed under different international and nationalistic scholarship and their agendas. Hopefully, it can also serve to critically reflect on the modes of current instrumentalization of medieval past in Spain’s public sphere and on the great value of Porter’s lessons on History of Art.

“Daily, bitter complaints are raised in Spain against the foreign culture that invades, drags, and drowns that which is authentic, pure, and is gradually burying, as the grumblers say, our national personality. The river, never dry, of the European invasion in our homeland increases its flow and course day by day, and at the present is overflowing, its swelling carries with the mill owners’ pain of the flooded dams and, perhaps, the wet flour. From some time now, Spain’s Europeanization has been precipitated.”1

Invasion, Civilization, or Melting-pot?

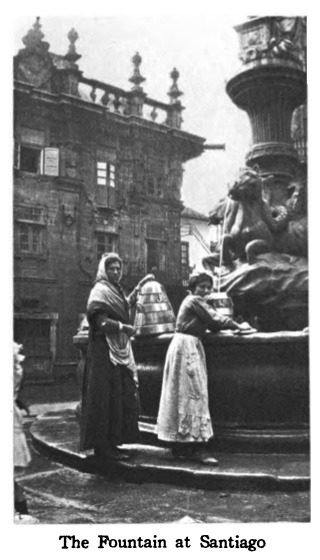

Almost prophetic, the opening words of the first chapter of En torno al casticismo (The Essence of Spain, 1902) by the famous Spanish writer Miguel de Unamuno (1864–1936)2 anticipate the ideological conceptions that, starting from the second decade of the twentieth century, the French and American academies would project in their “discovery” of the Romanesque art produced in Iberia and discussing its debts to the pilgrimage routes. Unamuno wrote about the “pain for Spain” derived from the so-called Disaster of 1898 and its consequences, dealing with the tensions between the national “castizo” and the “universal”, praising Cervantes’ Quijote. From France, the works of art historians such as Émile Mâle (1862–1954) and Paul Deschamps (1888–1974) proudly assumed the notion of a European (French) invasion of Spain condemned by Unamuno, presenting the peninsula as a barbaric space which had been necessarily civilized by France during the Middle Ages. In the words of Mâle, the road to Santiago “Was Spain’s road to civilization. It was through it that France’s most refined products reached Spain”.3Unlike Mâle, who never travelled to Spain, the Camino was toured – albeit with different means, comforts and gender handicaps – by two American scholars: Georgiana Goddard King (1871–1939) and Arthur Kingsley Porter (1883–1933) in the early 1920s.4 Although for King the Camino acquired more pronounced personal and romantic religious connotations than for Porter ― in her own terms, her project went “From a mere pedantic exercise in architecture, to a very pilgrimage” ― 5in Spain they both found the ideal setting to exalt a genuine spirituality lost for them with North America’s modernization. King described Compostela as “The end of heart’s desire […] like places to which you come in a dream and remember that you have known them long ago” [Fig. 1], while Porter was enchanted by Jaca’s pre-industrial beauty, which he defined as “One of the paradises on earth, as unspoiled as a beneficent God and inspired Middle Ages left it.”6

We do not know whether Porter ever read Unamuno, but in his Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads (1923), which celebrates its centenary this year, he used the river metaphor to describe the phenomenon of the pilgrimage to Compostela:

“The pilgrimage road may be compared to a great river, emptying into the sea at Santiago, and formed by many tributaries which have their sources in the far regions of Europe. All these streams, fathering as they descend, flowed together at Puente la Reyna, whence the river runs in its full strength to Compostela.”7

It is well known that, even if Porter criticized the nationalist conditioning from which Mâle wrote and his efforts to make Iberian Romanesque a product of French colonization ― of course, counter-arguing the primacy of the peninsular buildings over the Languedocian — his position was also far from neutral. Janice Mann already pointed out that Porter spoke of an art without nationality, “Neither French nor Spanish. It is the art of the pilgrimage”,8 where he found a fitting historical precedent for the cultural exchange produced by the floods of migrants arriving in the United States at his time. Borrowing the term “melting-pot”, the title of a contemporary play about the migration phenomenon, the way to Compostela was for him the place “In which artists from all over Europe met and exchange ideas”.9

The archaeologist and art historian Manuel Gómez-Moreno (1870–1970) was writing from Spain at the same time as Mâle, King and Porter, searching for the authenticity of the “Spanish genius” in medieval Iberian art.10 With Unamunian overtones in his suspiciousness over the Europeanizing consequences of the Camino, for Gómez-Moreno, the so-called Mozarabic art ― together with Jaca, León and Frómista, with an earlier dating according to him ― constituted that “Complex and disconcerted style like no other in Europe”,11 as opposed to a Romanesque style that, channeled by the pilgrimage routes, “Surrendered our personality for the sake of exotic institutions, standardizing us to the liking of the Cluniac and the pontifical legates”.12 In the preamble of his famous Mozarabic Churches (1919), he stated:

“Before the millennium, where very strong notes of our own genius can be detected, which then become confused and entangled under strange pressures, making their recognition and study much more difficult in successive periods” [Fig. 2].13

In this sense, the most French of all Romanesque Iberian churches, the cathedral of Santiago, evidently presented some limitations as an icon of a “Spanish” medieval art. Gómez-Moreno was thus taking part in an ongoing debate about what and who constituted “Spain” in the Middle Ages; and, above all, to what extent this supposed identity was undermined and/or exalted by the interaction with what was happening both in the south of the peninsula and beyond the Pyrenees. A year after Gómez-Moreno’s famous El arte románico español. Esquema de un libro (1934) was published, a young Meyer Schapiro (1904–1996) opened the knowledge of the illuminated manuscripts made in Iberia to international interest, showing to the French painter Fernand Léger (1881–1955) the Beato Morgan in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, a decisive encounter for the artist’s later pictorial work.14 It was not what was “Spanish” about Iberian Romanesque, but rather the pervasive topos of primitivism and the apparent taste for brutality of the paintings of Taüll and the copies of the Commentary on the Apocalypse that constituted a source of fascination for avant-garde artists such as Francis Picabia, Joan Mirò, Pablo Picasso and Robert Matta.15

The Promised Land

Another distant past, this time from the Old Testament, served both the poet Antonio Machado (1975–1939) and Miguel de Unamuno to project their “pain for Spain” at the beginning of the century. In La tierra de Alvargonzález (1912) and Abel Sánchez (1917) they respectively explored envy as a typically Spanish trait mirroring the story of Cain and Abel. The cliché of a “Cainite Spain”, envious and treacherous, condemned to cyclical fratricidal confrontation, not only permeated later post-war Spanish literature,16 but has recently been rhetorically revived by right-wing in Spain parties to criticize the Law of Democratic Memory (2022). The “Sons of Cain” were precisely the target of the pastoral Las Dos Ciudades, quoting St. Augustine’s De Civitate Dei, that the bishop of Salamanca, Pla i Deniel, published in September 1936 ― two months after the so-called “alzamiento nacional” by Franco’s regime.17 In the Spain of the dictatorship and the nationalistic discourse in which some of Gómez-Moreno’s later works saw the light of day, the ideological use of the Middle Ages permeated the rhetoric of the Civil War as the new modern crusade.18 Franco himself compared the war to a crusade where the “anti-Spain was defeated”,19 thus transferring not only the notion of a historical continuity rooted in the Christians who fought the religious enemy in the Middle Ages, but also identifying in them the seed of “Spain”, a nation in whose formation process Muslims and Republicans stood only as outsiders.

In addition to the ambiguous and complex relationship that the dictator established with the Muslims and the traces of their presence in the Iberian peninsula, it is significant that the first medieval heritage recovered by the regime was that of the Visigothic and Asturian past. In the victory mass celebrated in the Salesas Reales of Madrid on the May 29th, 1939, some of the most famous objects of the medieval “Spanish” past were exhibited.20 Among them, the Arca Santa of Oviedo was reactivated as the Ark of the Covenant possessed by the chosen people of God and transferred to the recently “reconquered” promised land. In the ceremony, Franco was anointed as the Old Testament priests and kings, following the Visigothic ritual and inventing for the occasion the musical notation of the prayers and blessings of two Mozarabic manuscripts: the tenth-century Antiphonary of León and the Liber Ordinum preserved in Silos. As Carmen Julia Gutiérrez recently studied, the use of the rite of anointing of kings of the Mozarabic liturgy sought to legitimize the dictator’s power through the continuity with the Visigoths, mirroring the restoration that Alfonso II undertook in Oviedo in the ninth century.21That city was again the scenario of power propaganda with the consecration of the Cámara Santa in 1942, where the Arca was carried out in procession on the shoulders of the bearers –following the transfer of its biblical prototype to the interior of Jerusalem described in I Chron 15:15 ― and during which Franco himself paraded holding the Victory Cross of Alfonso III. The mural painting commissioned to the Bolivian artist Arturo Reque Meruvia “Kemer” for the headquarters of the Institute of Military History and Culture in 1948 presented the dictator dressed as a medieval knight ― as a new Cid Campeador and hero of the undertaken modern crusade ―, surrounded by a sort of Sacra conversazione with his supporters in the war, and under the protection of the transfiguration of Santiago Matamoros.22 Beyond the military appropriation of the patron saint and his cult with slogans such as “arriba España” and “por el Imperio” on the posters of the Compostelan holy years, it is the link with the Visigothic and Asturian kings that seemed to concern the regime, which in its first steps showed little interest in Romanesque art and the pilgrimage phenomenon.

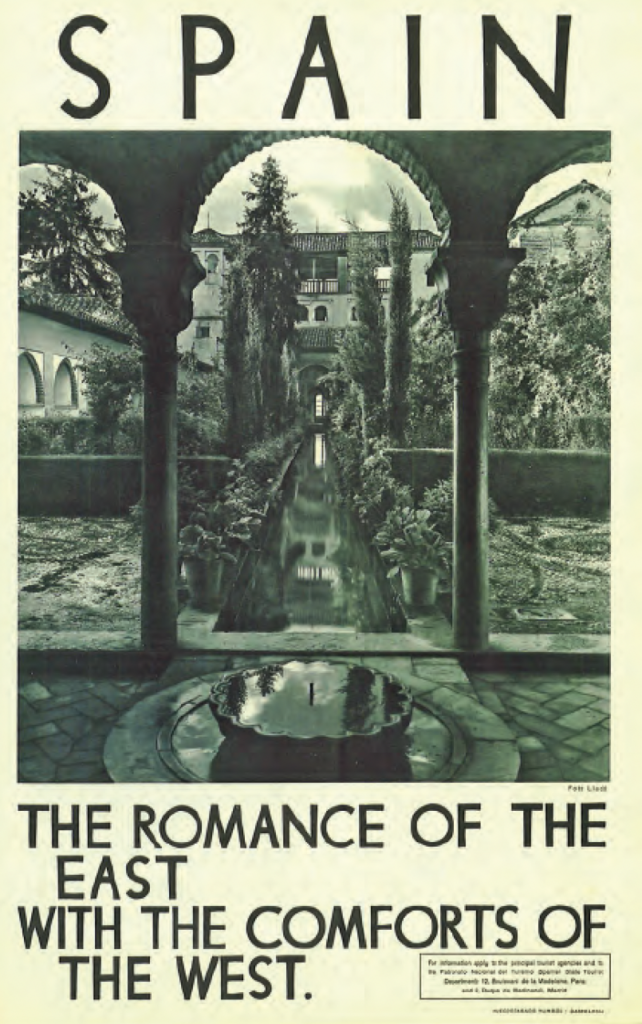

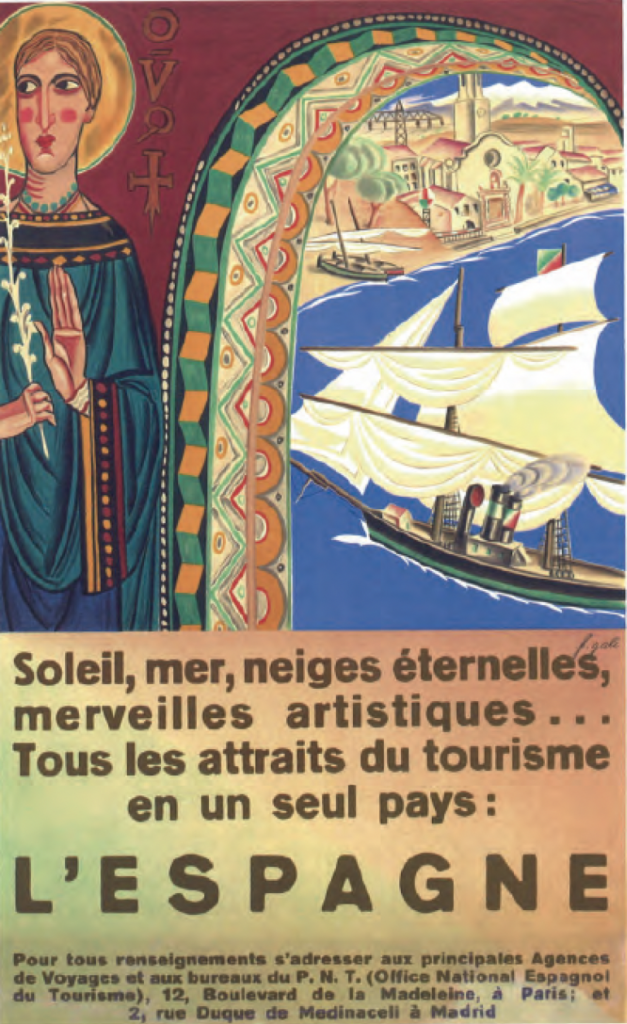

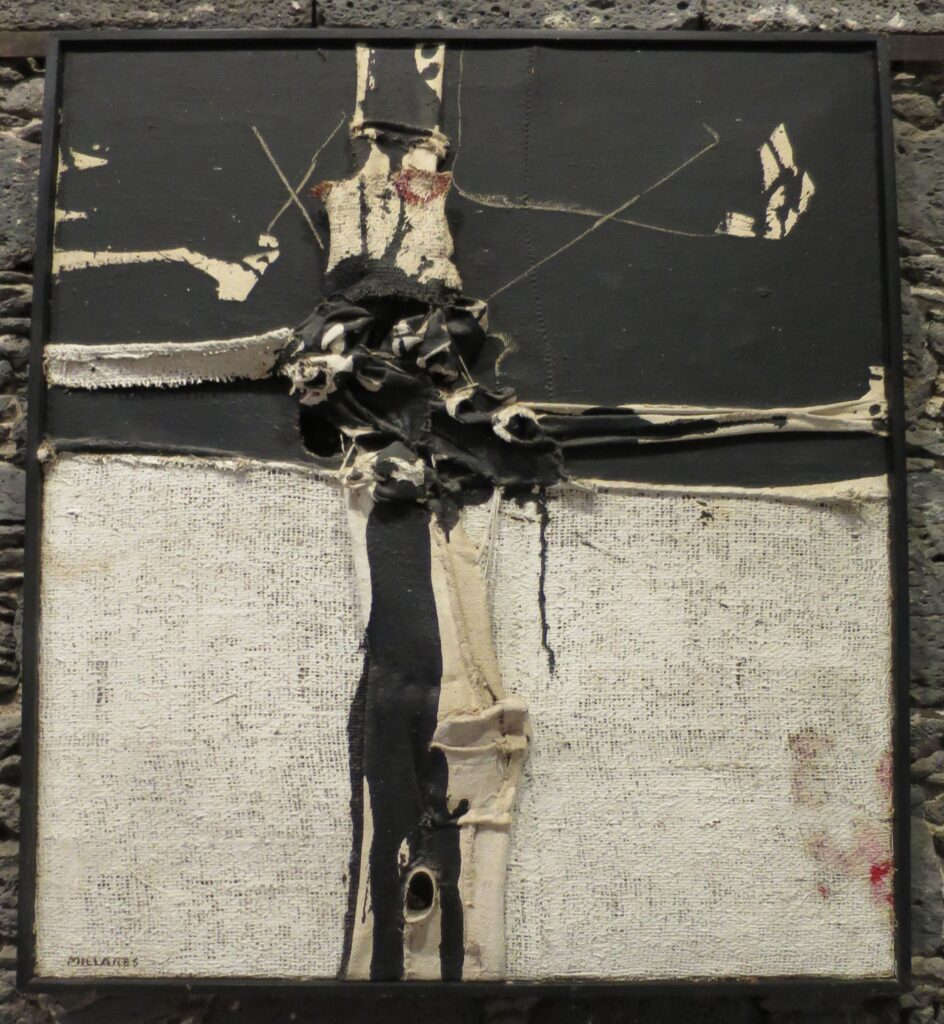

During the 1950s and 1960s, the whitewashing sought by the regime implied a turn in the type of art promoted by the Spanish State, from then on close to Informalism and aligned with the US capitalist democracy.23 Unlike the tourist posters promoted during Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship in the 1930s [Figs. 3–4], medieval monuments are almost absent in those designed under the famous slogan “Spain is Different” by the then Minister of Information and Tourism, Manuel Fraga. Spanish sun, beach and gastronomy displaced the Muslim and Byzantine exotism sold to the international tourism thirty years earlier.24

For the regime, medieval art (as any other) was valued as long as ― and only when ― it allowed to achieve certain political and ideological goals. The rapprochement to the United States after the pacts of 1953 was materialized in the shipment of the apse of the Romanesque church of San Martín de Fuentidueña to New York; an operation promoted by Gómez-Moreno himself to obtain a new position at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for her daughter Carmen. In 1961, she dedicated an article on Fuentidueña and its transatlantic journey.25 A year earlier, the MoMA exhibited the New Spanish Painting and Sculpture, with works by Canogar, Chillida, Cuixart, Millares, Saura and Tapiès, among others. Through the dark palettes and materials of Spanish informalists artists, Franco’s regime managed to sell the idea that Spain was as modern as New York and, at the same time, that its new artists were worthy successors to the tenebrism of the great Baroque painters, heirs of their religiosity and sobriety [Fig. 5].

Moreover, 1961 was also the year of The Cloisters’ opening in the presence of the Spanish ambassador, coinciding with the elaboration, this time before Europe, of a new narrative on the Camino de Santiago through the exhibition El arte románico (Barcelona and Santiago de Compostela), and a monographic issue of the journal Goya dedicated to the topic [Fig. 6]. The Camino and its art began to be, from then on, no longer an undermine to what was properly “Spanish” ― as for Gómez-Moreno ―, but the way to justify that Spain had been European at least since the end of the eleventh century.26 This renewed discourse on the pilgrimage routes would take its definite form during the democratic period, with the exhibition Santiago de Compostela, 1000 ans de pèlegrinage européen at the Europalia 1985 festival held in Brussels ― the same year in which Spain entered the European Economic Community ― and just two years before the proclamation of the Camino as the first European cultural itinerary.

A “Spanish” genealogy?

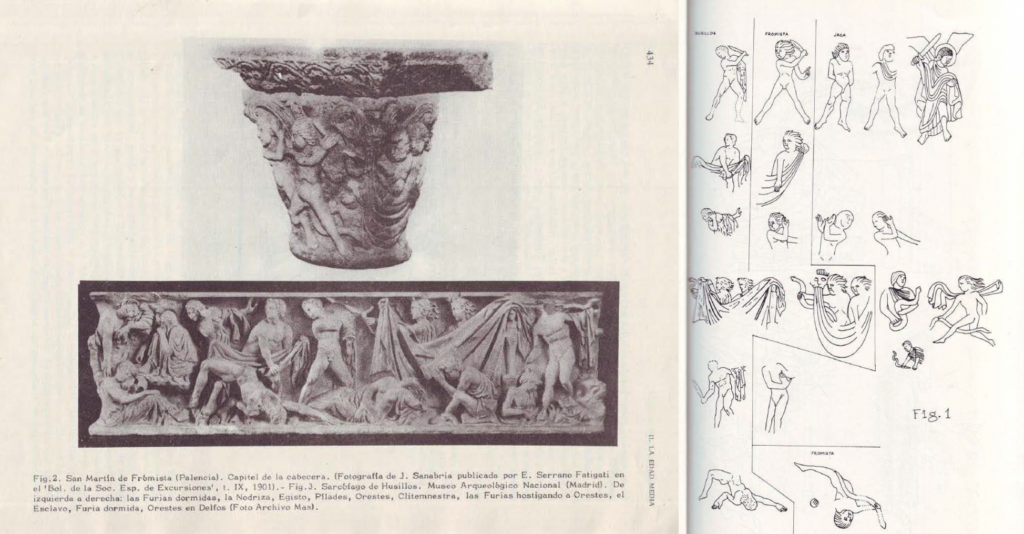

In the academic production of one of the most renowned Spanish art historians, Serafín Moralejo (1946–2011), we find another milestone in this tension to combine the national and the international, or to express the particular way in which the land of the exiled Sons of Cain could be European in its specificities. In 1977, the same year in which John Williams demonstrated that the link between the Muslims and Ishmaelites took shape in the tympanum of the Portal of the Lamb in San Isidoro de León,27 Moralejo traced another genealogy, that of the so-called “Frómista-Jaca style” from the Roman Oresteia sarcophagus, preserved in Santa María de Husillos (Palencia) at least since Ambrosio de Morales described it in the sixteenth century [Fig. 7].28 With it, Romanesque sculpture in Iberian soil finally had its own genetic history; a history which, however, was based on both international arguments and external factors: the appearance of the monumental sculpture in the trans-Pyrenean Romanesque temples had already been linked to the discovery of Antiquity and Late Antiquity in French historiography, and the sarcophagus of Orestes was, after all, an imported Roman piece.29 The circulation of the sculptors through Frómista, Jaca, Toulouse, León, and Santiago and its encounter there with non-Iberian artisans confirmed, for Moralejo, the potentiality of the pilgrimage routes as means for international creative encounters and exchanges, as Porter had already praised, while justifying at the same time the birth of Romanesque art in those places, in part, as an Iberian ― actually a Castilian ― experience, denying the territory a role of mere reception.30 In the Jacobean holy year of 1993, Moralejo curated the exhibition Santiago, Camino de Europa. Culto y cultura en la peregrinación a Compostela,31 and, at the same time, openly resisted to the Romanesque–Camino de Santiago binomial, arguing that the former would have existed in the peninsula without the latter, although perhaps “It would have lacked the integrality, monumentality, and consistency that came from its origins on the long Camino”.32

In 2010, again coinciding with the Jacobean holy year and, this time, also with the Spanish Presidency of the Council of the European Union, the exhibition Compostela y Europa: la historia de Diego Gelmírez was curated by one of Moralejo’s disciples, Manuel Castiñeiras, and traveled through Paris, Rome, and Santiago de Compostela in the image of the journeys carried out by the Compostelan prelate. The “European” travels of Gelmírez to Rome served Castiñeiras to explain the forms and contents adopted in the cathedral’s transept portals and presbytery, justifying the means by which a periphery became an authentic artistic center at the beginning of the twelfth century.33 The same author has alluded to the specific nature of Romanesque art: not exactly “local”, but also not conforming a “unity” with that of the rest of the European territory.34

The cloister of Silos has become, in this sense, one of the greatest battlegrounds.35 In Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads, Silos occupies an entire chapter and Porter dates its oldest part to the end of the eleventh century, thus making it precede Moissac. Although outside the Camino circuit, the presence of the shell of St. James in the pilgrim of Emmaus’ bag made the cloister “The earliest extant monument of pilgrimage art” for him.36 In his seminal article of 1939, Schapiro praised the monastery as a meeting place between the “Mozarabic” style, so dear to Gómez-Moreno, and the “Romanesque”. Writing from a Marxist perspective and reluctant to make Romanesque a French and Cluniac product, he looked into the political and social conditions of the peninsula and gave weight to the secular culture introduced into Silos by lay audiences.37 Very recently, the case of the first workshop of the cloister has served Gerardo Boto to demonstrate how a work of great quality, “avant-garde and specifically Hispanic”, does not participate in the Hispano-Languedocian style that Moralejo identified along the Camino, despite citing the pilgrimage phenomenon in its own sculptural content.38 This is just one example of the recent years’ questioning of the “art of the pilgrimage roads” paradigm and the limits of the role played by the cult of St. James in human movements and creative interchanges.39

From Covadonga to Granada

In the conclusion of his Contre l’art roman? (2006), Xavier Barral i Altet recalled the importance of reflecting on how contemporary events determine the gaze directed at the art of the Middle Ages, noting the impossibility of an objective and unmediated art history, made without interferences.40 The last few years of research have witnessed a revival of some of the questions Porter was already addressing in 1923. Although it seemed superseded, the “Spain or Toulouse” question is still tangentially touched upon each time the buildings involved are revisited, as shown, for instance, by Francisco Prado-Vilar’s consideration on the richness of the porta Francigena in Santiago41 or Ilene H. Forsyth’s dating for Moissac’s façade.42 On the other hand, the impact that the Muslim presence and the “frontier” situation ― practically ignored by Porter in Romanesque Sculpture ― had on the Christian art produced in Iberia has been explored since the 1990s especially by North American scholars: Jerrilyn Dodds, Julie Harris, Cynthia Robinson, Pamela Patton, Janice Mann, Elisabeth Valdez del Álamo and Therese Martin, among others. In 2021, the exhibition Spain 1000-1200. Art at the Frontiers of Faith, curated by Julia Perratore at The Cloisters, demonstrated the extent to which New York’s multicultural reality could try to find precedents in medieval Iberia. The authors’ defense of a territory where “People of different faiths and backgrounds regularly encountered one another and exchanged ideas”,43 and in which “The tension between separation and connection that characterizes these geopolitical regions became a source of creativity”44 updated in interreligious terms the melting-pot that Porter had limited to the Christian pilgrimage routes.

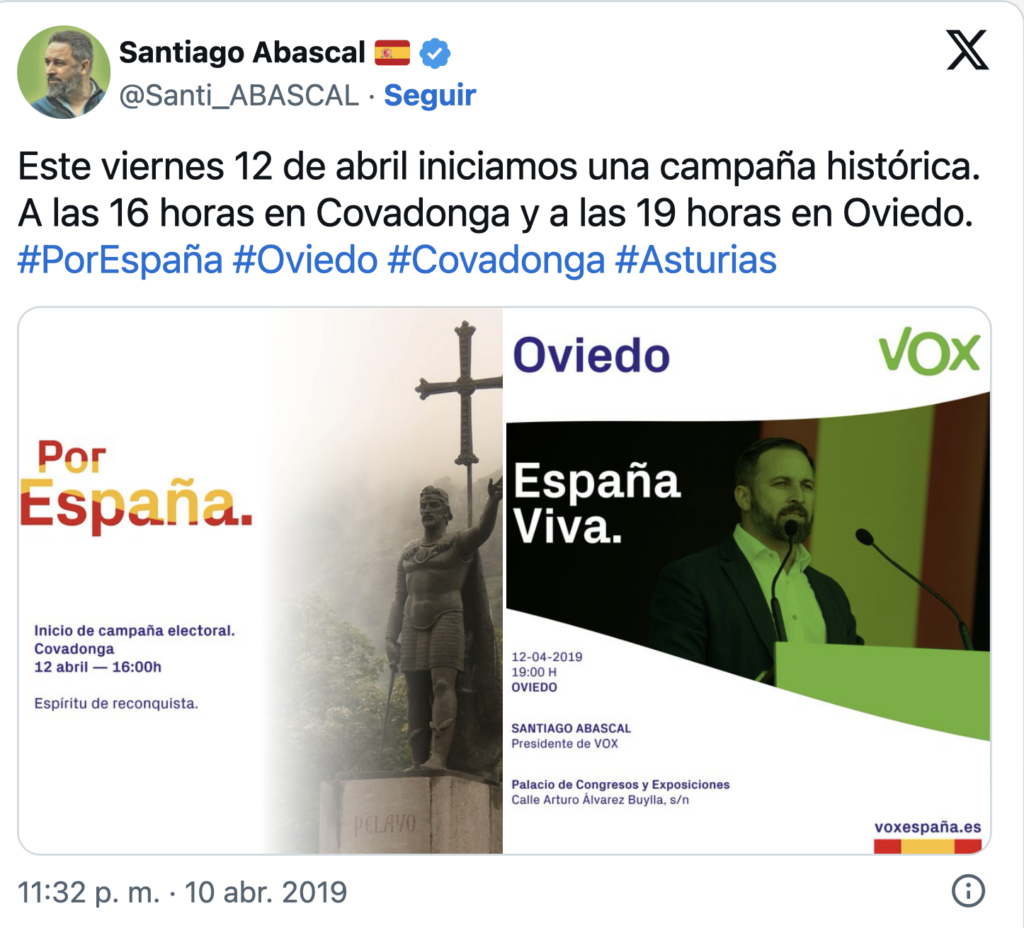

To conclude, two recent examples from the sphere of Spanish politics eloquently show the type of dialogues that are today taking place in Spain with the medieval past, the pilgrimage routes, and the Muslim presence in the peninsula, and how all can shape the uniqueness of a European country. In 2019, Santiago Abascal, leader of the far-right party VOX, began his election campaign in Covadonga and Oviedo, using the idea of the “Reconquest” for the first time so explicitly since Franco’s regime [Fig. 8].45 Every year, the anniversaries of the battle in Navas de Tolosa or the Christian conquest of Granada are an occasion for VOX to display on social media the pride for heroic battles thanks to which “Spain and Europe [both together] managed to free themselves from the Islamic invasion” [Fig. 9]. On the other hand, this same 2023, when Spain again holds the Presidency of the Council of the EU for the first time since 2010, the cultural program offered to the public does not include any references to the Camino ― perhaps considered sufficiently exploited with the double Jacobean holy year of 2021 and 2022, due to the health emergency of Covid-19.46 However, the leaders of fifty European countries met last October 5th in Granada and were received, first, by the Prime Minister and his wife in the Patio de Comares and, after, by the King and Queen of Spain in the Patio de los Leones of Alhambra. Welcoming Ukranian president Volodymyr Zelenski as guest of honor and remembering Federico García Lorca in the cradle of his birth, Pedro Sánchez made Granada the “European capital and the capital of peace” on his X (formerly Twitter) account [Fig. 10].

The anniversary of the publication of the ten volumes of Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads by Porter can definitely provide an opportunity to reflect on how medieval art produced in Iberia, the Camino, and the religious, cultural and political frontiers have been explored ideologically from inside and outside Spain since 1923. Nevertheless, the most precious lesson Porter left to our discipline is perhaps the one found in his foreword to his Spanish Romanesque Sculpture, published five years later:

“There can be little doubt that what we do today will seem equally quaint to an even near future. Classic works do not exist in this field. Its fascination, like that of flame, lies largely in the very fact that it is changeful and transitory. Successive arrows strike the bull’s eye; one may occasionally even reach it; with skill and practice we shoot nearer and nearer the mark; but who shall claim that his aim is infallible? New facts are constantly being acquired, and pass into the common heritage of the science; as the body of these acquisitions increases, older conceptions must be modified or discarded.”47

- “Elévense a diario en España amargas quejas porque la cultura extraña nos invade y arrastra o ahoga lo castizo, y va zapando poco a poco, según dicen los quejosos, nuestra personalidad nacional. El río, jamás extinto, de la invasión europea en nuestra patria aumenta de día en día su caudal y su curso, y al presente está de crecida, fuera de madre, con dolor de los molineros a quienes ha sobrepasado las presas y tal vez mojado la harina. Desde hace algún tiempo se ha precipitado la europeización de España”, Miguel de Unamuno, En torno al casticismo , Barcelona 1902, p. 130.[↩]

- About the problems of translating the Spanish “castizo” or “casticismo”, see Gerhard Masur, “Miguel de Unamuno”, The Americas , XII/2 (1955), p. 144.[↩]

- “Fut pour l’Espagne la route de la civilisation. C’est par là que lui arrivait ce que la France produisait de plus raffiné” Émile Mâle, “L’art du Moyen Âge et les pèlerinages. Les routes de France et d’Espagne”, Revue de Paris, XXVII (1920), pp. 788–789.[↩]

- Janice Mann, “Georgiana Goddard King and A. Kingsley Porter Discover the Art of Medieval Spain”, in Spain in America: The Origins of Hispanism in the United States , Richard L. Kagan ed., Illinois 2002, pp. 171–192.[↩]

- Georgiana Goddard King, The Way of Saint James, vol 1., New York/London, 1920, p. 22.[↩]

- Letter of Porter to Bernard Berenson, 24th May 1924, published in Janice Mann, “Romantic Identity, Nationalism, and the Understanding of the Advent of Romanesque Art in Christian Spain”,Gesta, XXXVI/2 (1997), p. 162.[↩]

- Arthur Kingsley Porter, Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads, vol. 1, Boston 1923, p. 175.[↩]

- Arthur Kingsley Porter, “Pilgrimage Sculpture”, American Journal of Archaeology, XXVI/1 (1922), p. 8.[↩]

- Arthur Kingsley Porter, “The Rise of Romanesque Sculpture”, AJA, XXII (1918), pp. 399–400; Janice Mann, “Frontiers and Pioneers: American Art Historians Discover Medieval Spain”, in Romanesque Architecture and Its Sculptural Decoration in Christian Spain, 1000–1120. Exploring Frontiers and Defining Identities, Toronto/Buffalo/London, 2009, pp. 29–30.[↩]

- Gerardo Boto Varela, “«Abrir a la curiosidad mundial esta España misteriosa». La historiografía ante el camino compostelano y la construcción de una identidad nacional”, in Antes y después de Antonio Palomino. Historiografía artística de identidad nacional, José Riello, Fernando Marías eds., Madrid 2022, pp. 71–83.[↩]

- Manuel Gómez-Moreno, Catálogo monumental de España. Provincia de León, Madrid 1925, p. 127. On the term “mozárabe” see Cyrille Aillet, “De l’usage du vocable «mozarabe» en Histoire médiévale”, Ménestrel, first published online in 2012, https://www.menestrel.fr/?-mozarabe-&lang=fr [last accessed 22/12/2023].[↩]

- Manuel Gómez-Moreno, Iglesias mozárabes: arte español de los siglos IX a XI, Madrid 1919, p. XIV.[↩]

- Manuel Gómez-Moreno, Iglesias mozárabes (n. 12), pp. X–XI.[↩]

- Francisco Prado-Vilar, “Silentium: el silencio cósmico como imagen en la Edad Media y la Modernidad”, Revista de poética medieval, XXVII (2013), pp. 21–26.[↩]

- Manuel Castiñeiras González, “Tre miti storiografici sul romanico ispanico. Catalogna, il Cammino di Santiago e il fascino dell’Islam”, in Medioevo: arte e storia. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi di Parma, 18–22 settembre 2007, Arturo Carlo Quintavalle ed., Milan 2008, pp. 97–99; Madeline H. Caviness, “The Politics of Taste. An Historiography of ‘Romanesque’ Art in the Twentieth Century”, in Colum Hourihane ed., Romanesque Art and Thought in the Twelfth Century. Essays in Honor of Walter Cahn, Princeton 2010, pp. 63–67; Juan José Lahuerta, “On the Futility of Comparisons: Notes on Picasso, Bohemia, Barbarism and Medieval Art”, in Romanesque–Picasso, idem ed., Barcelona 2016, pp. 34–95.[↩]

- Gemma Márquez Fernández, “La Biblia en la novela española de posguerra. La condena cainita frente a la redención evangélica”, in La Biblia en la literatura española, vol. III: Edad Moderna, Gregorio del Olmo Lete ed., Madrid 2008, pp. 413–450.[↩]

- See the recent edition: Glicerio Sánchez Recio, De las dos ciudades a la resurrección de España: magisterio pastoral y pensamiento político de Enrique Pla y Deniel, Alicante 2022.[↩]

- Francisco J. Moreno Martín, “Gesta Dei per hispanos.

Invención, visualización e imposición del mito de cruzada durante la guerra civil y el primer franquismo”, in La Reconquista. Ideología y justificación de la Guerra Santa peninsular, Carlos de Ayala, Isabel Cristina Ferreira Fernandes, José Santiago Palacios Ontalva eds., Madrid, 2019, pp. 483–518.[↩] - Jordi Carulla, Arnau Carulla, La Guerra Civil en 2000 carteles. República-guerra Civil-Posguerra, Barcelona 1996, p. 527.[↩]

- Moreno Martín, ”Gesta Dei per hispanos“ (n. 18), p. 502.[↩]

- Carmen J. Gutiérrez, “Francisco Franco y los reyes godos: la legitimación del poder usurpado por medio de la ceremonia y la música”, Cuadernos de Música Iberoamericana, XXXIII (2016), pp. 161–195.[↩]

- Moreno Martín, “Gesta Dei per hispanos” (n. 18), pp. 508–509.[↩]

- Julián Díaz Sánchez, “1960: arte español en Nueva York, un modelo de promoción institucional de la vanguardia”, Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte, XII (2000), pp. 155–166; Jorge Luis Marzo, “Tradition and Collaboration between the Avant-Garde and Francoism (1940–1960)”, Art in Translation, XII/2 (2021), pp. 150–184.[↩]

- Francisco Javier Lázaro Sebastián, “El cartel turístico en España. Desde las iniciativas pioneras del Patronato Nacional del Turismo hasta los comienzos del desarrollismo”, Artigrama, XXX (2015), pp. 143–165.[↩]

- Carmen Gómez-Moreno, “El ábside de San Martín de Fuentidueña” Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología, XXVII (1961), pp. 61–85. See the recent book by, José Miguel Merino de Cáceres and María Martínez Ruiz, De Fuentidueña a Manhattan. Patrimonio y diplomacia en España (1952–1961), Madrid 2023.[↩]

- Boto Varela, “«Abrir a la curiosidad»” (n. +10), pp. 86–92.[↩]

- John Williams, Generationes Abrahae. Reconquest Iconography in Leon”, Gesta, XVI/2 (1977), pp. 3–14.“[↩]

- Serafín Moralejo, “Sobre la formación del estilo escultórico de Frómista y Jaca”, in España entre el Mediterráneo y el Atlántico: actas del XXIII Congreso Internacional de Historia del Arte, vol. I., Comité Español de Historia del Arte ed., Granada 1977, pp. 427–434.[↩]

- On the sarcophagus see Aureliano Fernández-Guerra, “Sarcófago pagano en la Colegiata de Husillos, recién traído al Museo Arqueológico Nacional”, Museo Español de Antigüedades, I (1872), pp. 41–48; Antonio García Bellido, Esculturas romanas de España y Portugal, vol. I, Madrid 1949, pp. 212–217.[↩]

- “We may more properly speak of a ‘Camino de Santiago art’ beginning on the day that the principal sculptor of Frómista abandoned the workshop of that Castilian church and transferred his attention to Jaca” (Serafín Moralejo, “On the road: the Camino de Santiago”, in The Art of Medieval Spain, A.D. 500–1200, John Phillip O’Neill ed., New York 1993, p. 180).[↩]

- Santiago, Camino de Europa: Culto y cultura en la peregrinación a Compostela, catalogue of the exhibition (Santiago de Compostela, Barcelona, 1993), Serafín Moralejo and Fernando López Alsina eds., Santiago de Compostela 1993.[↩]

- Moralejo, “On the road” (n. 30), p. 182.[↩]

- Manuel Castiñeiras González, “El porqué de una exposición itinerante: Diego Gelmírez, genio y espíritu viajero del románico”, in Compostela y Europa. La historia de Diego Gelmírez, catalogue of the exhibition (Paris, Rome, Santiago de Compostela, 2010), Manuel Castiñeiras ed., Milan, 2010, pp. 16–29.[↩]

- Castiñeiras, “Tre miti” (n. 15), p. 92.[↩]

- Summarized in José Luis Senra, “Between Rupture and Continuity: Romanesque Sculpture at the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos”, in Current Directions in Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Sculpture Studies, Robert A. Maxwell, Kirk Ambrose, eds., Turnhout, 2010, pp. 141–167.[↩]

- Porter, Romanesque Sculpture (n. 7), p. 198.[↩]

- Meyer Schapiro, “From Mozarabic to Romanesque in Silos”, The Art Bulletin, XXI/4 (1939), pp. 349–351.[↩]

- Boto Varela, “«Abrir la curiosidad»” (n. 10), p. 100.[↩]

- See Paula Gerson, “Art and Pilgrimage: Mapping the Way”, in A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe, Conrad Rudolph ed., London, 2006, pp. 599–618.[↩]

- Xavier Barral i Altet, Contre l’art roman? Essai sur un passé réinventé, Paris, 2006, pp. 314–315.[↩]

- Francisco Prado-Vilar, “Flabellum: Ulises, la catedral de Santiago y la Historia del Arte medieval español como proyecto intelectual”, Anales de Historia del Arte, II (2011), p. 314.[↩]

- Ilene H. Forsyth, “The Date of the Moissac Portal”, in Current Directions in Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Sculpture Studies, Robert A. Maxwell, Kirk Ambrose eds., Turnhout 2010, pp. 77–100.[↩]

- Spain 1000–1200. Art at the Frontiers of Faith, exhibition catalogue, Julia Perratore ed., The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, LXXIX/2 (Fall 2021), p. 8.[↩]

- Spain 1000–1200, (n. 41), p. 11.[↩]

- Alejandro García Sanjuán, “Cómo desactivar una bomba historiográfica: la pervivencia actual del paradigma de la Reconquista”, in La Reconquista. Ideología y justificación de la guerra santa peninsular, Carlos de Ayala, Isabel Cristina Ferreira Fernandes, José Santiago Palacios Ontalva eds., Madrid 2019, pp. 110–117.[↩]

- https://spanish-presidency.consilium.europa.eu/es/presidencia/programa-cultural/[↩]

- Arthur Kingsley Porter, Spanish Romanesque Sculpture, vol. 1., New York, 1969 [1928], p. V.[↩]