It may seem surprising that the first article published on the new platform Critical Inquiries in Medieval Culture has apparently little to do with medieval culture as such. It deals, however, with figures of émigrés who have durably impacted the field of art history and who also happened to have left their footprint on the field of medieval art history. Above all, it deals with problems inherent to the medieval world and to the world in which we live: the movement of persons — forced or not — as a vector of cultural transfer, creativity, and transformation. Furthermore, this article originated with a reaction contextualized by ongoing work on emigration and art history.1

On September 26, 2022, on the occasion of the opening of the Centre for Modern Art & Theory at the Department of Art History, Masaryk University, Brno, Whitney Davis, professor at UC Berkeley gave a lecture with the title “Art History and the Tyranny of Humanism.” Borrowing as a title a remark from a famous essay by the late Hubert Damisch (1928–2017), Davis argued that a certain humanistic approach in art history leads to the impossibility to consider transhistorical or ahistorical contents in art history.2 This tyranny of humanism is, for Davis, mainly associated with the works of Erwin Panofsky (1892–1968), who defined art history as a humanistic discipline in the 1930s.3 The question Davis asks is if humanities are today serving the purpose of art history as a field, or if a different framework could prove more efficacious. This question springs, notably, from concerns with the negative effects of anthropocentrism chiefly on the environment and on marginalized social groups. Davis argues that a new approach, indebted to fields such as neuro-arthistory or eco-art history, could lead to an almost nomothetic (or better abstract) understanding of the phenomena, based on reductionism, and thus permitting to formulate general laws of understanding visual culture. What struck me were not so much these possibilities of a post-formalist or post-culturalist return to holistic art history, but rather Davis’ insistence on Panofsky’s humanism, to a certain degree extracting the idea from the historiographical context in which it was formulated.4 Davis scarcely recalled that Panofsky’s “History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline” was published amid the most consequential humanitarian crisis of the first half of the twentieth century. Tens of thousands of persons — Erwin and Dora Panofsky amongst them — were affected by closing borders, emigration policies, and profound violence towards the idea of humanity and freedom itself. Surely, discussing Panofsky’s legacy and formative role in the current debates around holistic vs. individualist approaches to art history explodes the frame of this contribution.5 How emigration has immediately affected art history and led to some of the most fertile exchanges of twentieth-century historiography is, however, a central question today, and one that has occupied me — alongside other colleagues — for some years already.6 A painfully burning actuality today but also historically for East-Central Europe, this topic makes it particularly difficult for me to accept deconstructing a certain form of humanism without being aware of its historical circumstances. Before entering the core of the article, I wish to precise that this text is by no means an advocation for humanism as such, and especially not its most problematic aspects — its central role in colonialism and crystallizing anthropocentrism and Eurocentrism, for example.7 Much rather, it is a reflection on figures who went through dramatic and profoundly transformative experiences and on the compelling perspectives they developed as a result of these experiences.

In the wake of recent political events, from pandemics to border restrictions, the return of war and populism in Europe, Russia, and the US, with frontiers closing and movement of persons becoming hindered by policies and historical circumstances, the direct impact of the movement of persons for the history of art history must, indeed, be recalled with strength. In this frame, it seems to me particularly crucial to recall from a historiographical perspective that the traumatic experiences of many émigré art historians had a direct impact on their work, and on the ways in which this work was implemented in their host countries.8

The present contribution focuses on the impact of closed frontiers and immigration policies in the tragic period of the 1930s when the need to emigrate became more and more evident for populations and individuals directly threatened by the rise of totalitarian regimes. I will, in the first part, briefly recall the problematic role of emigration policies, especially in the United States. In the second part, I will recall the stories of art historians who emigrated, and the impact of this experience on their scholarly engagement. Ultimately, I wish to open the question of art historians’ shifting engagement with societal issues through the impactful experience crossing frontiers had on their intellectual framework. How much, indeed, can we still learn today from the experiences of émigrés at a moment when the field of art history and visual studies itself has radically expanded and is in urgent need of reassessing its place and role within society?

Emigration or death: crossing borders as an economic,

administrative, and racial problem

Many Americans still proudly call the United States a “nation of immigrants”.9 Without entering into the history of this problematically whitewashing idea and its more recent political appropriations, numbers can speak: it is estimated that between 1900 and 1914, around 12 million European indeed emigrated to the US to try their luck in the “New World”.10 Thus demonstrated, immigrants certainly made it to the US, but the nation’s immigration policy is historically unwelcoming due to the many inherent and overt biases incorporated into law. In the interwar years and 1930s, within a rapidly changing political situation, such experience reached its paroxysm as millions of persons were obliged to move, directly threatened in their physical, religious, and intellectual integrity by the rise of totalitarian regimes. After first tightening immigration policies in the US between 1918 and 1933, notably because of racial and political reasons (fear of “racial contamination” of the American population and Communists) and because of the economic impact of the 1929 Great Depression, the situation became increasingly difficult.11 This situation deeply affected German émigrés in these years.

With the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany, discrimination against Jews and enemies of the party began immediately, shattering the brief but fertile culture of Weimar and causing an unprecedented wave of immigration.12 A large proportion of the emigrants fled not only for their lives, but also to escape the progressive disappearance of intellectual, scientific, and cultural activity not aligned with the National Socialist Party’s goals. In a movement of cultural purge almost unprecedented until then, the only activities authorized were those that contributed directly to Nazi political and cultural propaganda. Artists, writers, academics, and scientists were either directly — as with the April 7, 1933 Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service (Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums) and its infamous third paragraph which dismissed Jewish professors — or indirectly obliged to leave to continue to enjoy academic freedom, often adapting their activities and language to potential host countries.13 With the extension of the Nazi regime to Austria and Czechoslovakia, a similar wave of exodus emanated from these countries as well. The traumatic decision to emigrate with no certain return was darkly recontextualized by the horrific state of the years 1938 to 1942 when the Nazis gradually moved from a policy of persecution and forced emigration to a policy of annihilation of the Jewish population.14 In October 1941, Germany banned emigration and began to outline its eradication program. Those who had escaped lived not only with the trauma of displacement but with the knowledge of this programmatic annihilation in their former homeland.15 Some months later, in January 1942, in a luxurious villa in the Berlin suburbs on Lake Wannsee, fifteen Nazi leaders — presided over by Heinrich Himmler’s deputy, Reinhard Heydrich — decided that the policy of forced emigration was not effective enough to deal with the Jewish question. A solution, which involved the relocation of all Jews from the territory to the East and their gradual or immediate extermination in camps, was to be implemented as soon as possible.16 After 1942, any emigration, any border crossing could thus only be illegal and became a matter of life and death. As history has shown, only a fraction of people managed to escape these deportations and the effectiveness of the criminal regime after 1942.

The US had remained a place of ideal (and idealized) escape. But for all the above-mentioned reasons, in 1933 the American government issued visas to a meager 1,241 Germans, although 82,787 people were on the German waiting list for an American visa.17 Most of these people, mostly Jews, were too poor to qualify for immigration and thus found themselves on waiting lists that could last 3 to 4 years, often too long to escape persecution. Between 1934 and 1937, there were between 80,000 and 100,000 Germans on waiting lists for an immigration visa, a number that increased further and reached a peak in 1940, with over 300,000 people on the waiting list. The rules for obtaining the visas, both from the Nazi regime and the American government, were draconic, including heavy taxes, the obtention of a myriad of certificates, as well as financial sponsors in the host country. In addition to these formalities, it should be remembered that the medical checks already carried out in Europe were also repeated by American doctors upon arrival, where people often had to wait in quarantine for up to several weeks before finally being allowed to enter the territory. Before it was used by the US Navy in 1939, many migrants found themselves waiting in the facilities of Ellis Island. Here, medical examinations became a means of enforced control but also manipulation through psychological and physical humiliation as well as the financial extortion of the migrants, both on departure from Nazi Germany and on arrival in the US.18 Failure to present documents or to meet certain criteria resulted in being sent back to Europe. Even passengers who had their documents in order were not guaranteed entry to the territories of the US. This is exemplified by the story of the infamous liner St. Louis, which left the port of Hamburg in May 1939 carrying mostly Jewish refugees [Fig. 1].

The passengers aboard the St. Louis had visas for Cuba, but due to recent changes in policies, they were refused. They were then denied refuge by the US and Canada, and the ship had to make a U-turn back to Europe, eventually landing the passengers in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Britain. It is estimated that around thirty percent of the ship’s passengers were subsequently deported and died in the camps.19

In the best cases, it was, thus, only at the end of a process that can only be described as financially and mentally exhausting that one could hope to obtain the precious visa stamp, to turn to the many other economic, personal, and social challenges that awaited the new emigrants. After 1940, with Europe at total war, new restrictions came into force, and with the entry of the United States into the conflict in 1941, waiting lists were simply canceled.

Individual stories, personal engagements

It is within such a framework that the emigration of intellectuals must be placed. Art historians and other academics had it slightly easier than most: an impressive number of people in Germany at that time had not only existing networks but also artistic or scientific talent that would serve them well as capital in their host country.20 German and Austrian universities and researchers were indeed often at the forefront of international research in fields as diverse as astrophysics, psychoanalysis, or art history. Although a minority in the population (ca 1%), Jews were also prominent among these elites: one in eight university professors was Jewish, and a quarter of the German Nobel Prizes had been won by German Jews.21 Most interestingly, the percentage of Jews in the field of art history itself was remarkably high: ca. one-quarter of art historians in Germany and Austria were of Jewish origin.22

Legally or illegally emigrating to countries such as England, France, or the USA, thousands of German and Austrian architects, lawyers, artists, doctors, filmmakers, journalists, and publishers arrived in England and in the US throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, often along tortuous routes, depending on the availability of visas and often only narrowly escaping the authorities’ controls.23 The Nazi regime was pushing its paradox of moral and racial purity at the cost of a huge loss of intellect — astrophysicists, doctors, leading intellectuals — resulting in an immediate cultural impoverishment, transforming Germany into a conformist state that repressed most intellectual and artistic innovation. Among the host countries, the US occupied a special place. What had been “Hitler’s loss” became “Hitler’s gift”, a story of refugees and intellectual emigration with consequences that are still well palpable today.24 German academia and science were, in a certain way, to become “Americanized” and gradually made accessible to a wider public.25 John Peale Bishop, who wrote in 1941 about the future of the arts in the US, argued that German scholarship would have a long-term impact on American culture at large:

“The presence among us of these European writers, scholars, artists, composers, is a fact. It may be for us as significant a fact as the coming to Italy of the Byzantine scholars, after the capture of their ancient and civilized capital by Turkish hordes. The comparison is worth pondering. As far as I know the Byzantine exiles did little on their own account after coming to Italy. But for the Italians their presence, the knowledge they brought with them, were enormously fecundating.” 26

This comparison with the Byzantine world in exile is indeed worth pondering. For several centuries, Constantinople had been perceived as the center of the world and the sole heir to the Roman Empire. It had been envied, attacked, plundered, imitated, but remained prestigious. Peale Bishop’s metaphor seems to indicate a similar desire on the part of American elites to access the treasures of a somewhat mythical city: but as with Italians and “Byzantium”, this occurred through a simultaneously activated binary between welcoming receptivity and cultural rejection.

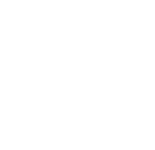

Within this constellation, art history was literally transformed in the US by emigrants. A few key figures that had professionalized the discipline in Europe were the same art historians and their pedagogic progeny who later emigrated to the US.27 Panofsky — to return to him — wrote as early as 1940 that for him the transformation and wide success of art history were linked to the “providential synchronism between the rise of Fascism and Nazism in Europe and the spontaneous efflorescence of the history of art in the United States”.28Of Jewish descent, Panofsky and his wife Dorothea Mosse (1885–1965) had arrived in 1931, never to return to Germany. A disciple of two founding figures of German art history who already had a profound impact on American art history, Wilhelm Vöge (1868–1952) and Adolph Goldschmidt (1863–1944), Panofsky had benefited from the excellence of an Interwar German academic education and was already a full professor when he was forced to move to and then remain in the US. It was in New York and then at Princeton University, after he had begun first to teach and then to write in English, that he experienced large success: Panofsky had succeeded in combining German erudition with the mastery of English rhetoric, and his lectures and talks were attended by a vast audience of students and amateurs [Fig. 2].29

Of course, art history was already well established in American universities and was, to a certain extent, ready to receive the impulse of the émigrés.30American-style art history (and other fields) had often drawn on continental models not only in the methods, but also in the development of academic programs, museum practices, and related productions.31Figures such as Vöge or Goldschmidt themselves, for example, but also more controversial ones such as Josef Strzygowski (1862–1941), had been involved in the development of art history as a full-blown discipline, especially after the 1914–18 war.32 But proportionately few German professors had emigrated to the US permanently, despite the opportunities. It was thus the forced emigration of German art history from the 1930s onwards that contributed to the profound renewal of the American art history system.

Two personal stories of emigrants whose individual trajectories differ, but who both had a major impact on the history of American and world art and architecture help to highlight this movement, oscillating between involuntary exile and fertile acculturation: Richard Krautheimer and Ernst Kitzinger.

From Germany to the United States, with some detours

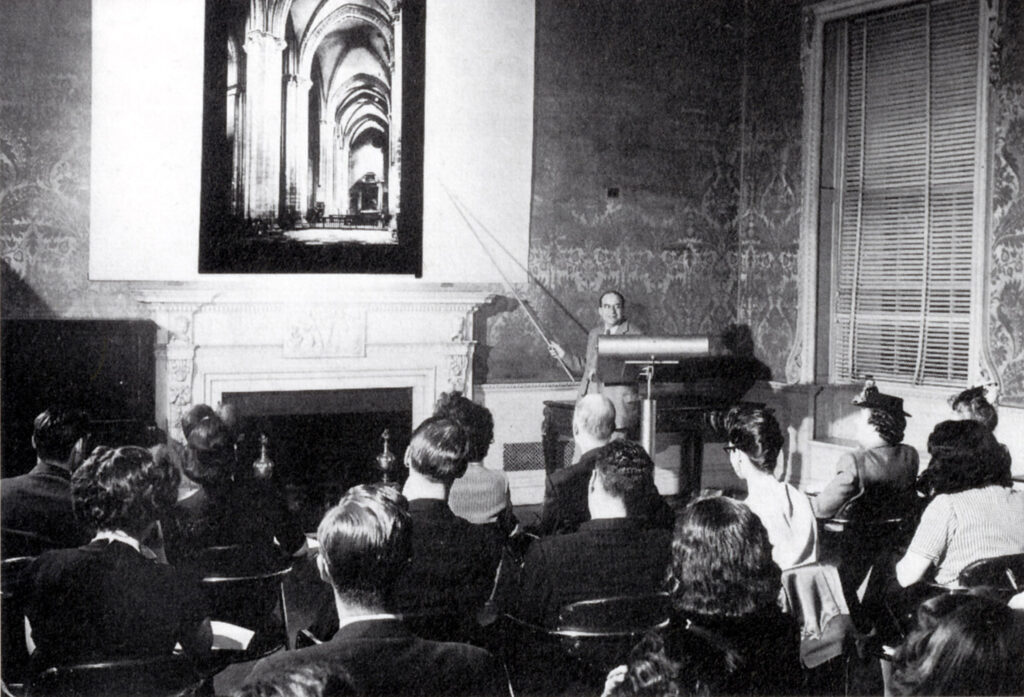

Like Panofsky, Richard Krautheimer (1897–1994) remains one of the most widely read and influential architectural historians of the twentieth century in Europe and the US. [Fig. 3]33 From a Jewish family, Krautheimer was born on 6 July 1897 in Fürth, a Bavarian town adjacent to Nuremberg with a large Jewish community since the fifteenth century. Raised in a religious but liberal family, young Richard benefited from the good upbringing of a bourgeois German Jewish family in those years. During the 1914–18 war, Krautheimer fought as a German patriot, experiencing the Great War in the Somme and then along the Siegfried Line. After the war and having been humorously judged by his father as “too stupid to become a merchant”, Richard chose the path of studies.34 First at the University of Munich, where he studied with Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945) and Paul Frankl (1878–1962), then in Berlin with Adolf Goldschmidt, Richard Hamann (1879–1961) in Marburg, and finally in 1923 for his thesis and doctoral examinations at the University of Halle, where Frankl had meanwhile become a full professor. 35)In 1924 he wrote a thesis on the churches of the mendicant orders in Germany in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, which he successfully defended, and then embarked on a long journey to Italy. The latter was also to be a wedding trip since he had married Trude Hess (1902–1987) — also an art historian — in 1924. It was in Italy that he met not only the monuments of the Eternal City for the first time, but also Ernst Steinmann (1866–1934), the director of the Bibliotheca Hertziana, the city’s prestigious German art history institute. It was during this trip and in the following years that the first milestones were set for a monumental work on the churches of the city of Rome from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages, which was to occupy Krautheimer for the rest of his life. At the University of Marburg, Krautheimer was to obtain his habilitation to teach under Prof. Richard Hamann. The habilitation happened not with a study on late medieval gothic sculpture that he had prepared and which Hamann did not want to read (and whose manuscript was later lost), but with his 1927 book on medieval synagogues.36 It is a book that was perhaps born, in a certain way, from a desire of reconnecting with a Jewish past in the difficult years leading to the election of Hitler. Krautheimer repeatedly describes this book as full of errors and incomplete because he did not read Hebrew.37 In a sadly prophetic way, this interest in Jewish religious heritage led to a listing and careful study of a series of religious buildings that would mostly be demolished in the years to come. In Krautheimer’s hometown of Fürth alone, the main seventeenth-century synagogue and six other synagogues were destroyed in 1938 during Kristallnacht.38 All Jews from Fürth who remained in Germany were deported and condemned to die in the camps.

And then, after a few years of teaching as a Privatdozent in Marburg, in 1933, there was suddenly no room at the German university for Krautheimer and many others.39 It is difficult to judge how much the professor apprehended the gravity of the political situation in the first months. But in February 1933 he wrote to his fellow art historian Fritz Saxl (1890–1948) — later the first director of the Warburg Institute — that he needed “an hour and a half each morning to recover from reading the newspapers”.40 Although as a war veteran he could have stayed on for a few more months, even being qualified as a non-Aryan, on May 11 Krautheimer wrote a heavy-hearted letter to the Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Marburg. In this letter, as for thousands of other German Jews, the deep disappointment of a German citizen to see Hitler’s anti-regime at the head of his country transpires:

“Your Excellency,

I beg you to believe that it will be very difficult for me to write the following lines: I would like to ask you to grant me a leave of absence until further notice. I could truthfully justify this request by saying that I would like to complete my studies on the ancient Christian basilicas of Rome […] But these justifications are overshadowed by considerations whose gravity your Excellency can measure by the fact that I have struggled for weeks to make this decision. […] I beg Your Excellency to understand the conflict I face as a German and as a Jew. On the one hand, nothing would be more desirable for me than to work for my part in Germany and for Germany; on the other hand, I am perfectly aware that at present students do not grant a Jew, even if he feels very German, the trust which is the indispensable prerequisite of any authentic teaching activity.”41

From his words, one understands Krautheimer’s disappointment and hopes that this is only a temporary situation.42 And we also understand his desire not to wait to be ousted from his position, but to try to distance himself from the German situation — at least temporarily. Thus, theoretically, Krautheimer was never dismissed, but was effectively allowed a lifetime leave. As early as 1933, his first instinct was to turn to Italy not only for refuge — as about 18,000 Jews and 2,000 other emigrants did in that year – but also for the love of art history. Before the implementation of racial and anti-Semitic laws in Italy in 1938, the prospect of living under Mussolini’s Nationalist Fascist Party and still being able to study the monuments of the Italian peninsula seemed less terrible. Krautheimer stayed first in Florence and then in Rome, but German institutes — even abroad — were obliged to exclude Jews from their activities. Thanks to the intervention of the director of the Hertziana and a network of emigrants and refugees being established in Rome, Krautheimer could continue to stay and work there, at least for a while. This was only possible under the auspices of institutes that had more freedom from the regime in Germany, especially the Pontifical Institute of Christian Archaeology (Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana), which had been founded by Pope Pius XI in 1925. The Catholic priests Johann Peter Kirsch (1861–1941), the first rector of the Institute, and Joseph Wilpert (1857–1944), an illustrious German Christian archaeologist, enabled Krautheimer to continue his activities almost uninterruptedly.43 As he recalls in his memoirs, working on the corpus of the churches of Rome in those years was “[…] the best thing that could have happened to me at that point. It was something to hold on to, and it forced me to stick to it day to day […]”.44 Krautheimer also recalls that the intellectual climate in Rome was fascinating because emigration had brought together scholars and intellectuals from different backgrounds: Jewish emigrants, anti-fascist Italians, anti-Nazis, and foreign scholars rubbed shoulders with each other. Often out of fear, however, most Germans had “dropped [the emigrants] like a hot potato”.45

In 1935, despite a (fortunately) unsuccessful attempt to stay in Rome on an American scholarship, Richard and Trude Krautheimer emigrated to the US. A special program for talented emigrants enabled him to find a teaching position in the US. However, this position was not in cosmopolitan New York, but in Louisville, a city in Kentucky. There, art history was an unknown discipline; there were no specialized books on the subject, and history itself began in the late eighteenth century when the first American settlement was established in the area. Krautheimer was to remedy the problem of book collecting with a generous grant from the Carnegie Foundation. The collection of books and slides (indispensable tools for the practice of art history since the beginning of the twentieth century), acquired for Louisville by the German émigré, still forms the basis of the art history department today.46 A second problem of immigration presented itself in this setting: language. Krautheimer had never taught in English and had to learn a new language to teach – a more direct, more flexible language than German according to the researcher.47 As for Panofsky, this transition from academic German to English would allow access to art history to a larger number of people than ever before. Nourished by newspapers, American films, and discussions with colleagues and students, Krautheimer quickly mastered this new obstacle and learned to teach a whole new audience: these students in Louisville were intelligent and alert, but from a completely different culture, far from the historicized, polyglot, religiously rooted view of Europe.48

After this initial encounter, Krautheimer received a position — thanks to privileged contacts — at Vassar College, some 120 kilometers north of New York, along the Hudson. There, teaching and contacts with the elite of art historians and intellectuals — emigrants or not — in New York were easier. At the same time, until 1938, the Krautheimers were still able to travel to Rome to study each summer. In 1940, with solid studies of medieval architecture under his belt, which are still routinely cited today, Krautheimer claimed that he had become “part of American art history.”49 From the words of Krautheimer’s text, one understands that for the émigré, the sense of belonging here lies in an oscillation between peer recognition and acculturation and understanding of a close but significantly different mentality and culture. With the entry of the US into the 1939–45 war in December 1941, the Krautheimers became American nationals: at forty-four, Richard Krautheimer was too old for active military service, but in 1942 and until 1944, he worked alongside his pedagogical and academic activities in the Office of Strategic Services as an analyst of aerial photographs of Rome, with the task of preventing the destruction of historical monuments by bombing. Thus, perhaps poetically, a Bavarian-born, now American professor who knew the topography of Rome very well, was working to preserve a city that had been bombed out of the throes of a totalitarian regime.

After the war and those turbulent years, Krautheimer’s career is already historicized widely: he had a long and fertile career in the US, professor from 1952 at the prestigious Institute of Fine Arts of New York University, and from 1971 in Rome, where he spent his old age in a flat directly within the Bibliotheca Hertziana. An eloquent documentary produced by the Louvre Museum in 1991 shows him, now in his nineties, crossing the Eternal City to visit the excavation site of a Roman church that he was then still studying. Significant for a man who lived through the barbarity of the Nazi regime, his last words in the documentary are an indirect quote of those of Cassiodorus, who founded a monastery in Vivarium, Calabria, in the sixth century and oversaw copying classical Latin texts during the Gothic invasions. Krautheimer says: “I know that the barbarians are going to come and there are things I want to save for the future. And that’s why we are working today, because we see the barbarians at the gates.”50

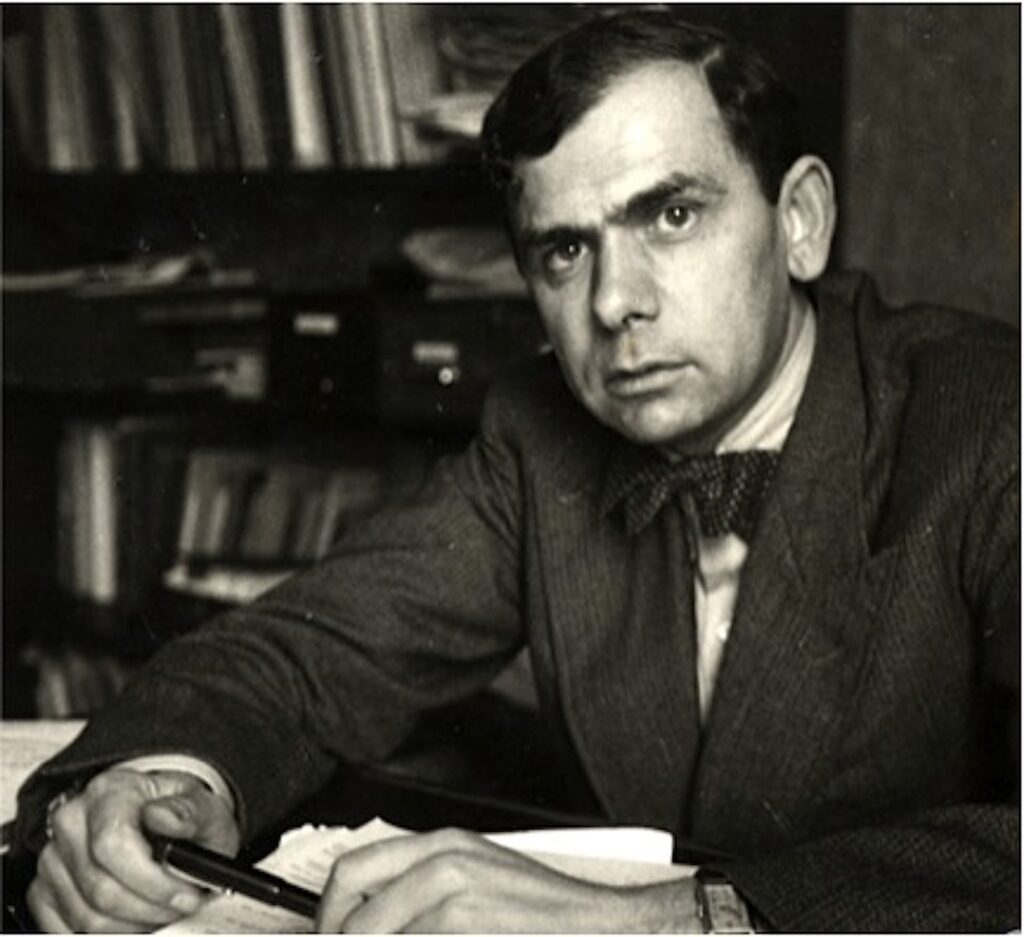

As recalled recently in a historiographical volume, the experience of emigration was significant for yet another famous émigré art historian, Ernst Kitzinger (1912–2003), a major figure in twentieth-century medieval art history [Fig. 4].51 Kitzinger, born into a Jewish family in Munich, studied from 1931 onwards mainly under Wilhelm Pinder (1878–1947), before a trip to Rome which turned his interests towards the art and architecture of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages.52 It is in Rome, at the German institute of art history, the Bibliotheca Hertziana, that his path crossed for the first time that of Krautheimer: how could these two persons imagine that they would both spend a good part of their lives in exile in the US? Krautheimer was already a professor at this time, but the rise of the regime was catastrophic for younger Jewish students as well. They risked not being able to finish their studies or not having their diplomas recognized: Kitzinger, therefore, rushed to finish his doctoral thesis with Wilhelm Pinder as quickly as possible, writing it in only one year and defending it by autumn 1934. The very next day he emigrated.

After a brief stay in Rome, Kitzinger arrived in London, with the opportunity to work as a volunteer and later as an assistant in the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities of the British Museum. In London, he would meet his future wife, Susan Theobald Ranby (1915–2000), and try to make a name for himself and a career as a young emigrant scholar. Despite his precociousness, Kitzinger brought the professional and theoretical perspective of German art history to British art history — which was usually in the antiquarian tradition and previously dominated by amateur scholarship. This led to important studies refreshing the field of Anglo-Saxon art, from the tomb of St. Cuthbert to the Anglo-Saxon crosses and the sensational excavations at Sutton Hoo in 1939. Kitzinger was present when the objects from the Sutton Hoo hoard arrived in London, and he signed some of the fundamental preliminary studies on the subject.53 Thanks to his position at the British Museum, he had the opportunity to visit Egypt and to stay in Istanbul for the first time during these years.54It was there that he was able to see for the first time the Byzantine mosaics of Hagia Sophia, which were being freed from their plaster coating and restored beginning in 1931.55The young Kitzinger was also able to make a name for himself: his Early Medieval Art in the British Museum, published in 1940 as a guide to the objects in the British Museum, is in fact a highly innovative text that examines the profound transformation of ancient styles around the Mediterranean towards the medieval aesthetic.56

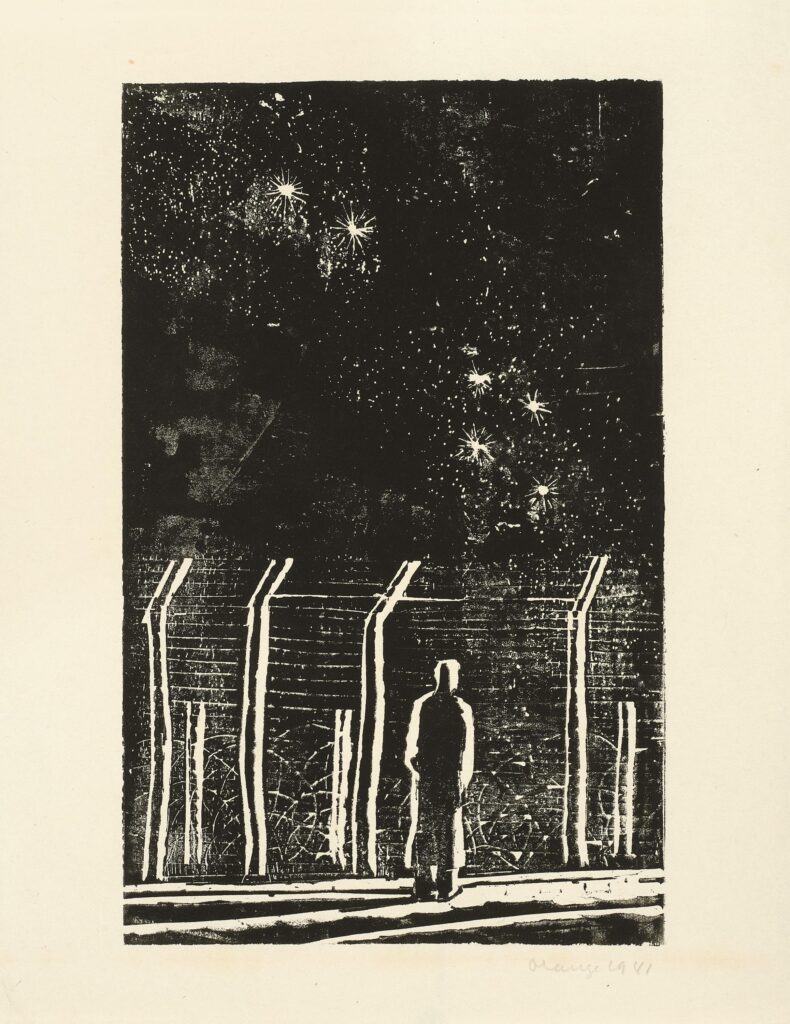

The same year as this publication, the decision came from the British authorities that Kitzinger, a Jew who had fled the Nazi regime, was to be interned by the British government. Following the German invasion of France in June 1940, Kitzinger — like most of the German, Austrian, and Italian citizens resident or visiting England — was interned. While these measures were primarily intended to isolate potential spies from emigrants who had fled Nazism, the operation was conducted en masse, and distinctions were lost when the emigrants were arrested. It was therefore by what could be termed a “bureaucratic error” that Kitzinger was first evacuated to two temporary camps in England, before being put on board the Dunera, a military transport ship bound for Australia.57 The ship, which left Liverpool on July 10, 1940, was packed. With 2,542 prisoners on board, plus crew and guards, the ship was almost double its original capacity of 1,600 passengers.58 The majority of the passengers were, like Kitzinger, German Jewish refugees, with some German prisoners of war and some allegedly fascist Italians. Barely two days after leaving the English coast, the ship was very nearly sunk by a German submarine. In addition to the risks, and even though most of the passengers were innocent, they were treated like prisoners: the guards were brutal, frequently mistreating the passengers, confiscating all their possessions and throwing most of the luggage overboard. Sanitary and human conditions on board were deplorable during the voyage of almost eight weeks (10 July – 6 September 1940) to Sydney. Reading descriptions of the journey, one can imagine the shock of moving from the halls of the British Museum to the corridor of a ship.59 He was not the only prominent refugee on board. He was in the company of eminent researchers, intellectuals, engineers, musicians, etc., including the painter and Bauhaus teacher Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack (1893–1965), the nuclear physicist Hans Kronberger (1920–1970), and the opera singer Erich Liffmann (1914–1987), to name but a few. After a first stop in Melbourne, the ship continued to Sydney, before a nearly 19-hour train ride ahead to Hay, a village about 720 kilometers inland to the west of Sydney. The landscape was desert-like, with temperatures frequently above 40°C and intense drought. The men were separated into two camps surrounded by barbed wire, as rendered in a melancholic woodcut by the aforementioned Hirschfeld-Mack [Fig. 5]. Despite harsh conditions, bonds formed between “prisoners”, ranging from football games to impromptu concerts that even attracted the local population — who listened from the other side of the fence. In addition, in-house universities were organized, with courses ranging from languages to physics: in a tragic but also poetic turn of events, Kitzinger taught medieval art history in the middle of the Australian desert.60

Fortunately, for Kitzinger and most of the other “Dunera Boys”, as they would later call themselves, this experience was short-lived. Pressure from many institutes and individuals who objected to the British government’s unjust decision ensured that it quickly realized the error of its ways, allowing the people to return. The Australian government offered some to stay in Australia, and almost a thousand remained — among them the Austrian art historian Franz Adolf Philipp (1914–1970), who contributed to the development of the art history department at Melbourne University, as well as Hirschfeld-Mack.61 Kitzinger, who had been helped by his colleagues at the Warburg Institute in London, left Australia after nine months in June 1941, returning to Britain a free man. Kitzinger’s Australian interlude offers us another personal story that might seem like a rocky adventure to us today. Yet, this experience is the reality for many people around the world. Bearing this in mind, what can we learn from this brief interlude? It is impossible to judge whether these nine months had a lasting impact on Kitzinger’s thinking and life. But perhaps more than anything else, it reminds us, despite the privileged position of many emigrants, of the fragility of their situation and the precariousness of their place in British society. Acculturation, even with considerable intellectual capital, did not mean becoming part of the host society.

This is perhaps why, like Krautheimer, Kitzinger’s journey would take him further west. Already in December 1941, a few months after his return from captivity, Kitzinger became a Fellow in Byzantine Studies at the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection – a prestigious study center in Washington, D.C. founded a few years earlier by the American philanthropists Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss.62 After a brief interlude during the war, during which he was — again like Krautheimer — an analyst for the Office of Strategic Services in Washington and London, Kitzinger’s American career was all set: back at Dumbarton Oaks in 1946, he became a professor of Byzantine art and archaeology, becoming over the years one of the most important art history professors of his generation. From 1955 to 1966, he was Director of Byzantine Studies at Dumbarton Oaks: it was during these years that Dumbarton Oaks became one of the world’s leading institutions for Byzantine studies. This had been possible, once again, thanks to the presence of many other European emigrants, among whom, to name but two, the Russian Alexander A. Vasiliev (1867–1953) — who had also been the president of the Kondakov Institute in Prague — and the Czechoslovak Catholic priest František Dvorník (1893–1975), an eminent specialist in Slavic and Byzantine history.63 In this exceptional place of knowledge that united emigrants from the Old Continent, national borders were somehow erased by common studies and, perhaps, by the joy of returning — at least in intellectual exchange — to a Europe not torn apart by war and strife.

Wary watchtowers: Humanism is not Anthropocentrism

From Panofsky to Krautheimer and Kitzinger, a series of scholars trained in pre-war and interwar German discipline were obliged to acculturate themselves to a new world, one prepared to receive art history and its methods as a discipline in its own right. It is clear today that American (and by extension international) art history would not be the same without this influx of emigration itself. Of course, this is not only true for art history. Émigré scholars did not only “invent” or produce studies and students by themselves: they encouraged innovation by attracting new researchers to their field, at the same time increasing the productivity of existing researchers.64 Methods were imported and adapted to the American context.

The historical material these researchers studied also inevitably became a mirror of their present moment, an observation which returns us to the first part of this paper. It was certainly no surprise, as we have already seen above with Krautheimer, that Panofsky, Kitzinger, but also other famous émigrés such as Ernst Cassirer (1874–1945), Kurt Weitzmann (1904–1993), or Paul Oskar Kristeller (1905–1999) suddenly became interested in the values and figures who had been responsible for the development of humanities in Europe. Displaying not only a deep interest in figures such as Erasmus and Dürer but also in Neoplatonism and the idea of “Renaissance” in a broader sense, they opened new research into humanistic subjects. Whether it was the “Carolingian” renaissance in the eighth-ninth centuries, the “Macedonian” renaissance in the ninth-tenth centuries, or the humanist renaissance, these scholars were concerned with the idea of the ‘survival’ and transformation of culture through the ages.65 While these were subjects they had sometimes touched upon as early as the 1920s, the idea of a sudden rebirth, a revival after a “dark” or “decadent” age resonated directly with scholars who had been driven out by a truly brutal regime that mobilized the ancient or medieval past — but in a distorted way, as a justification to glorify some and exclude others.

Fascination with such ideas responded in part to the fear of exclusion and pressures of acculturation in the US, and was perhaps, for Jewish scholars, compounded by the difficulties engendered by the arduous emancipation of Jewish scholarship in Germany. In their research and because of their experience crossing frontiers only to find themselves stranded in front of closed doors, the emigrant art historians were expressing a wish: the preservation of culture and humanity even in impossible times. And it is, I believe, precisely this drive toward the preservation of a shared culture across the borders established by individuals and political regimes that we must retain today from the traumatic and transformative experience of the émigrés in the 1930s and 1940s. Panofsky, amongst other émigrés and thinkers, thus elected “humanism,” as problematic a term as it may be, as an ideal of humanity in solidarity against totalitarian regimes. The role of a humanist, no matter the specialization and country, was, in this sense, clear: to fight with all means available against regimes, which were misappropriating history and visual culture as weapons of oppression, exclusion, and racialization. In rejecting Panofsky’s humanism, we lose the lesson, the knowledge, of the forcefully displaced émigré.

Of course, there is no questioning that art history, today, should reject the universalizing, dominant imperialist ideal of a monoculture born out of humanist concepts.66 But, in the end, I would like to come back to Panofsky’s unfortunate image of the ivory tower, which has shed much ink especially because of the colonialist implications of this expression in the US.67 Today, we feel perhaps that the tower dweller of this metaphor, secluded from others, tries to reach out to those on the ground, but rarely makes a real impact. We must recall Panofsky’s own words in defense of this idea: “The tower of seclusion, the tower of equanimity – this tower is also a watchtower. Whenever the occupant perceives a danger to life or liberty, he has the opportunity, even the duty, not only to ‘signal along the line from summit to summit’ but also to yell, on the slim chance of being heard, to those on the ground.”68 Despite the slim chance, of which Panofsky was clearly aware in 1957, this image is compelling as to the role of art historians, and intellectuals at large, in the twenty-first century. By getting rid of the towers of humanism, we forget the crucible in which they formed: between emigration policies and closed borders. We should clearly dissociate the problem of humanities per se and the compelling perspectives originating from the dramatic and profoundly transformative experience of emigration.

Dissecting “humanism” does not mean striking down the watchtower. In doing so, we could be cutting off a tradition of standing up against totalitarianisms, authoritarianisms, and injustice. The history of émigré art historians in a broad sense compels me to disagree with the idea put forward by prof. Whitney Davis: humanism is, I believe, not a tyranny, as long as humanism transforms with our times. The anthropocentricity of humanism and humanities has had a devastating impact on non-human actors, certainly. But the turn to post-humanism in a time of surging fascism and populism is unsurprising. Ignoring the contributions of humanist discourse masks the rise of totalitarianism. A new hybrid must be conceived between anthropocentric and ecocentric studies. An inclusive humanism, not a humanism of dominant monoculture, preoccupied those displaced scholars who lived through the horrors of the Nazi regime. Humanism cannot exclude others, and when it is stripped of its most problematic aspects (colonialism, Eurocentricism, anthropocentrism), it becomes a possibility to reenvisage a fight against all forms of tyrannies, including that of closed borders and failure to understand that migration and exchange are forming the very core of modern art history.

- This article was written within the project Potenciál migrace. Přínos (nejen) ruských emigrantů meziválečné Evropě, Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (TL02000495).[↩]

- Hubert Damisch, Théorie du nuage. Pour une histoire de la peinture, Paris 1972, “Le problème, pour la théorie, est de ne pas céder à la tyrannie d’une humanisme qui ne voudrait connaître des produits et des époques de l’art — comme de tout autre fait humain — que dans leur singularité, leur individualité, et qui tiendrait pour illégitime, voire inadmissible, la recherche des invariants, des constances historiques et/ou transhistoriques à partir desquelles le fait plastique se laisserait définir dans sa généralité, sa structure fondamentale, et dont la production théorique apparaît comme la condition d’une histoire de l’art rigoureuse, sinon scientifique”.[↩]

- Erwin Panofsky, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline”, in The Meaning of Humanities , T. M. Greene ed., Princeton 1940, pp. 89–118; on the text: Barbara Baert, Signed ‘PAN’: Erwin Panofsky’s

(1892-1969) ‘The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline’ (Princeton, 1938), Leuven/Paris/Bristol 2020.[↩] - Whitney Davis, “Visuality and Vision: Questions for a Post-Culturalist Art History”, Estetika, 54 (2017), pp. 238–257. In the same volume, see the reaction by Hans Christian Hönes, “Reconnecting with Culture: a Reply to Whitney Davis”, pp. 258–266.[↩]

- Branko Mitrović, “Humanist Art History and its Enemies: Erwin Panofsky on the Individualism–Holism Debate”, Konsthistorisk tidskrift/Journal of Art History, 78/2 (2009), pp. 57–76; idem, “A Panofskyan Meditation on Free Will and the Forces of History: Is Humanist Historiography Still Credible?”, Journal of Art Historiography, 15 (2016).[↩]

- Adrien Palladino, “The Wolfgang Born–Kondakov Institute Correspondence: Art History, Freedom, and the Rising Fear in the 1930s”, Convivium, VI/2 (2019), pp. 128–135; idem, “Transforming Medieval Art from Saint Petersburg to Paris: André Nikolajevič Grabar’s Fate and Scholarship between 1917 and 1945”, Convivium Supplementum(2020), pp. 122–143; Ivan Foletti, Adrien Palladino, Byzantium or democracy? Kondakov’s legacy in emigration: the Institutum Kondakovianum and André Grabar, 1925–1952,Rome 2020; Ivan Foletti, Adrien Palladino, “Nomadic Arts in Emigration:

Russian Diaspora, Czechoslovakia, and the Broken Dream of a Borderless Europe (1918–45)”, Journal of Art Historiography, 25 (2021).[↩] - Slavica Jakelić, “Humanism and Its Critics”, in The Oxford Handbook of Humanism, Anthony B. Pinne ed., New York City 2021, pp. 265–293.[↩]

- Colin Eisler, “Kunstgeschichte American Style: A Study in Migration”, in The Intellectual Migration: Europe and America, 1930–1960, Donald Fleming, Bernard Bailyn eds, Cambridge, MA 1969, 544-629; Die Künste und die Wissenschaft im Exil 1933–1945, Edith Böhne, Wolfgang Motzkau-Valeton eds, Gerlingen 1992; Karen Michels, “Die deutschsprachige Kunstgeschichte im Exil”, Kunsthistorische Arbeitsblätter, 3 (2006), pp. 43–52; eadem, Transplantierte Kunstwissenschaft ¬– Deutschsprachige Kunstgeschichte im amerikanischen Exil, Berlin 1999; Kevin Parker, “Art History and Exile: Erwin Panofsky and Richard Krautheimer”, in Exiles and Emigrés, The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, Stephanie Barron ed., Los Angeles 1997, pp. 317–325.[↩]

- On this problematic idea: Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Not ‘A Nation of Immigrants’: Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and a History of Erasure and Exclusion, Boston 2021.[↩]

- Timothy J. Hatton, Jeffrey G. Williamson, “What Drove the Mass Migrations from Europe in the Late Nineteenth Century?”, Population and Development Review, XX/3 (1994), pp. 533–559.[↩]

- Timothy J. Hatton, Jeffrey G. Williamson, “What Drove the Mass Migrations from Europe in the Late Nineteenth Century?”, Population and Development Review, XX/3 (1994), pp. 533–559.[↩]

- For numbers: Lars Nebelung, Sylvia Rogge-Gau, Claudia Zenker-Oertel, “Die Liste der jüdischen Residenten in Deutschland, 1933–1945”, Mitteilungen aus dem Bundesarchiv, 14 (2006), pp. 59–66; Nicolai M. Zimmermann, “The List of Jewish Residents in the German Reich 1933–1945”, Federal Archives of the Bundesrepublik Deutschland. See also Jean-Michel Palmier, Weimar en exil: le destin de l’émigration intellectuelle allemande antinazie en Europe et aux États-Unis, 2 vols, Paris 1988.[↩]

- Michael Grüttner, “The Expulsion of Academic Teaching Staff from German Universities, “1933–45”, LVII/3 (2022), pp. 513–533.[↩]

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution, London 2008.[↩]

- Studies have shown that both Jewish and non-Jewish Germans were clearly aware of the events as early as 1942. The bibliography on this question is vast, see: Peter Longerich, ‘Davon haben wir nichts gewusst!’ Die Deutschen und die Judenverfolgung 1933–1945, Munich 2006; Carolin Dorothée Lange, “After they Left: Looted Jewish Apartments and the Private Perception of the Holocaust”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, XXXIV/3 (2020), pp. 431–449.[↩]

- On Wannsee and the gradual decision and implementation of the “final solution”, see Peter Longerich, Politik der Vernichtung: eine Gesamtdarstellung der nationalsozialistischen Judenverfolgung, Munich 1998; idem, Wannseekonferenz. Der Weg zur ‘Endlösung’, Munich/Berlin 2016.[↩]

- Richard Breitman, Alan M. Kraut, American Refugee Policy and European Jewry, 1933–1945, Bloomington 1987.[↩]

- Fairchild, Science at the Borders (n. 11).[↩]

- Sarah A. Ogilvie, Scott Miller, Refuge Denied: The St. Louis Passengers and the Holocaust, Madison 2006.[↩]

- Pierre Bourdieu, “Les trois états du capital culturel”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 30 (1979), pp. 3–6.[↩]

- Tom Ambrose, Hitler’s Loss. What Britain and America Gained from Europe’s Cultural Exiles, London/Chester Springs 2001, p. 16.[↩]

- Karen Michels, “Art History, German Jewish Identity, and the Emigration of Iconology”, in Jewish Identity and Modern Art History, Catherine M. Soussloff ed., Berkeley, CA 1999, pp. 167–179.[↩]

- The Intellectual Migration. Europe and America, 1930–1960, Donald Fleming, Bernard Bailyn eds, Cambridge, MA 1969; Anthony Heilbut, Exiled in Paradise: German Refugee Artists and Intellectuals in America from the 1930s to the Present, New York 1983; Sabine Eckmann, Caught by Politics: Hitler Exiles and American Visual Culture, New York 2007.[↩]

- See Ambrose, Hitler’s Loss (n. 21) and Jean Medawar and David Pyke, Hitler’s Gift: Scientists who Fled Nazi Germany, London 2000. See also Antonin Cohen, “Les ‘émigrés scholars’ dans la genèse transatlantique des études européennes”, in Les études européennes: genèse et institutionnalisation d’un objet d’étude, Fabrice Larat, Michel Mangenot, Sylvain Schirmann eds, Paris 2018, pp. 27–50.[↩]

- Wolf Lepenies, “Exile and Emigration. The Survival of ‘German Culture’”, in The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Harvard University 1999, pp. 161–205; Erwin Panofsky, “Three Decades of Art History in the United States: Impressions of a Transplanted European”, College Art Journal, XIV/1 (1954), pp. 7–27.[↩]

- John Peale Bishop, “The Arts”, The Kenyon Review, III/2 (1941), pp. 179–190, 184.[↩]

- Eisler, “Kunstgeschichte American Style” (n. 8); Michels, “Die deutschsprachige Kunstgeschichte” (n. 8).[↩]

- Panofsky, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline” (n. 3), pp. 108–109.[↩]

- William S. Heckscher, “Erwin Panofsky: A Curriculum Vitae”, Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, XXVIII/1 (1969), pp. 4–21; Jan Białostocki, “Erwin Panofsky (1892–1968): Thinker, Historian, Human Being”, Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, IV/2 (1970), pp. 68–89; Irving Lavin, “American Panofsky”, in Migrating Histories of Art: Self-Translations of a Discipline Migrating Histories of Art: Self-Translations of a Discipline Erzwungener Ausweg: Hermann Broch, Erwin Panofsky und Ernst Kantorowicz im Princetoner Exil, Darmstadt 2008; Karen Michels, “‘Pineapple and mayonnaise – why not?’: European Art Historians meet the New World”, in Darmstadt 2008; Karen Michels, “‘Pineapple and mayonnaise – why not?’: European Art Historians meet the New World”, in The Art Historian: National Traditions and Institutional Practices, Michael F. Zimmermann ed., New Haven 2003, pp. 57–66.[↩]

- E.g., Kathryn Brush, “The Unshaken Tree: Walter W. S. Cook on Kunstwissenschaft in 1924”, in Seeing and Beyond: A Festschrift on Eighteenth to Twenty-First Century Art in Honor of Kermit S. Champa, Deborah J. Johnson, David Ogawa eds, Bern [i.a.] 2005, pp. 329–360; The Early Years of Art History in the United States. Notes and Essays on Departments, Teaching and Scholars, Craig H. Smyth, Peter M. Lukehart eds, Princeton 1993; Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, “American Voices. Remarks on the Earlier History of Art History in the United States and the Reception of Germanic Art Historians”, Ars, XLII/1 (2009), pp. 128–152, republished in Journal of Art Historiography, II (2010).[↩]

- German Influences on Education in the United States to 1917, Henry Geitz, Jürgen Heideking, Jurgen Herbst eds, Cambridge / New York 1995.[↩]

- Kathryn Brush, “German Kunstwissenschaft and the Practice of Art History after World-War I: Interrelationships, Exchanges, Contexts”, Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft, 26 (1999), pp. 7–36; eadem, “Adolph Goldschmidt in the ‘Wilds’ of 1920s America”, in Adolph Goldschmidt (1863–1944). Normal Art History im 20. Jahrhundert, Gunnar Brands, Heinrich Dilly eds, Weimar 2007, pp. 183–207; eadem, The Shaping of Art History: Wilhelm Vöge, Adolph Goldschmidt, and the Study of Medieval Art, Cambridge 1996; Christopher S. Wood, “Strzygowski und Riegl in den Vereinigten Staaten”, Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte, 53 (2004), pp. 217–234.[↩]

- On Krautheimer’s early biography, see recently Ingo Herklotz, Richard Krautheimer in Deutschland. Aus den Anfängen einer wissenschaftlichen Karriere 1925–1933, Münster / New York 2021. See also autobiographical notes: Richard Krautheimer, “And Gladly Did He Learn and Gladly Teach”, in Rome. Tradition, Innovation and Renewal, Clifford M. Brown, John Osborne, W. Chandler Kirwin eds, Victoria, B.C. 1991, pp. 93–126.[↩]

- Krautheimer, “And Gladly Did He Learn” (n. 33).[↩]

- See Herklotz, Richard Krautheimer in Deutschland (n. 33[↩]

- Richard Krautheimer, Mittelalterliche Synagogen, Berlin 1927.[↩]

- Bibliotheca Hertziana archive, estate of Richard Krautheimer, letter to Prof. Peter K. Klein, 12.10.1994 (RK 8/4): “das unglückselige ‘Synagogen’-Buch […] (unglückselig, denn es ist einfach schlecht, die Fakten sind nicht untersucht, und zudem konnte ich sie gar nicht untersuchen, weil ich Hebräisch nicht kann)”.[↩]

- Barbara Eberhardt, Frank Purrmann, “Fürth”, in, vol. 2: Mittelfranken, Wolfgang Kraus, Berndt Hamm, Meier Schwarz eds, Lindenberg 2010, pp. 266–333.[↩]

- Herklotz, Richard Krautheimer in Deutschland (n. 33), pp. 318–52.[↩]

- “Jeden Morgen brauche ich anderthalb Stunden, um mich von den Zeitungen zu erholen”, London, Warburg Institute Archive, Richard Krautheimer, General correspondence, 1934, cited in Herklotz, Krautheimer in Deutschland (n. 33), p. 344.[↩]

- “Ew. Spektabilität, bitte ich mir glauben zu wollen, daß es mir sehr schwer wird, die folgenden Zeilen zu schreiben: ich möchte Ihnen darin die Bitte vortragen, mir bis auf weiteres Urlaub zu bewilligen. Ich könnte diese Bitte wahrheitsgemäß damit begründen, daß ich meine Studien über die altchristlichen Basiliken Roms zum Abschluß bringen möchte […] Aber ich stelle diese Begründungen hinter Erwägungen zurück, deren ganze Schwere Ew. Spektabilität daran ermessen mögen, daß ich wochenlang um diese Entscheidung gekämpft habe. […] Ich bitte Euer Spektabilität den Konflikt verstehen zu wollen, dem ich als Deutscher und als Jude gegenüberstehe. Auf der einen Seite wäre mir nichts erwünschter, als für meinen Teil tätig in und für Deutschland zu wirken; auf der anderen Seite aber bin ich mir völlig klar darüber, daß im Augenblick die Studentenschaft als solche einem Juden, mag er sich noch so sehr als Deutscher fühlen, das Vertrauen nicht entgegenbringt, das die unerläßliche Voraussetzung jeder echten Lehrtätigkeit ist”, from Marburg, Universitätsarchiv, 307d, Nr. 2455, cited in Herklotz, Krautheimer in Deutschland (n. 33), pp. 345–346.[↩]

- More on this: David Kettler, “‘Erste Briefe’ nach Deutschland: zwischen Exil und Rückkehr”, Zeitschrift für Ideengeschichte, 2 (2008), pp. 80–108.[↩]

- Orte der Zuflucht und personeller Netzwerke. Der Campo Santo Teutonico und der Vatikan 1933–1955, Michael Matheus, Stefan Heid eds, Freiburg im Breisgau [i.a.] 2015; Herklotz, Krautheimer in Deutschland (n. 33), pp. 353–384.[↩]

- Krautheimer, “And gladly did he learn” (n. 33), p. 98.[↩]

- Ibidem, p. 99.[↩]

- Ibidem, pp. 99–100. On the importance of slide collections for teaching art history: Robert S. Nelson, “The Slide Lecture, or the Work of Art History in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, Critical Inquiry, XXVI/3 (2000), pp. 414–434.[↩]

- Krautheimer, “And gladly did he learn” (n. 33), pp. 104–105.[↩]

- Krautheimer recalls his surprise when a student asked him, referring to the nimbus of the Virgin: “But who is that lady with the straw hat?”, in Krautheimer, “And gladly did he learn” (n. 33), p. 100. For another experience of emigration, see Kurt Weitzmann, Sailing with Byzantium from Europe to America: the memoirs of an art historian, Munich 1994.[↩]

- Krautheimer, “And gladly did he learn” (n. 33), p. 104.[↩]

- “Richard Krautheimer: Journées romaines”, realized by Philippe Collin, Série Entretiens du Louvre, 1991. Filmed in the Italy of Berlusconi, Krautheimer continues: “I shouldn’t say this, but the barbarians now are perhaps television”.[↩]

- Ernst Kitzinger and the making of medieval art history, Felicity Harley-McGowan, Henry Maguire eds, London 2017. See also Henry Maguire, “Ernst Kitzinger: 1912–2003”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, LVII (2003), ix–xiv; Hans Belting, “Ernst Kitzinger: 27. Dezember 1912 – 22. Januar 2003; Gedenkworte für Ernst Kitzinger”, Reden und Gedenkworte / Orden Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaftern und Künste[↩]

- Sandra Steinleitner, “Ernst Kitzinger und der Beginn seiner kunsthistorischen Laufbahn in seiner Heimatstadt München: biografischer Überblick und Stand der Forschung”, Münchner Beiträge zur jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur, VI (2012), pp. 23–33.[↩]

- Ernst Kitzinger, “The Sutton Hoo Finds: The Silver”, British Museum Quarterly, 13 (1939), pp. 118–26.[↩]

- On Kitzinger’s London years: John Mitchell, “Ernst in England”, in Ernst Kitzinger and the Making (n. 51), pp. 15–37 and Felicity Harley-McGowan, “From London to the Antipodes: The Peregrinations of Ernst Kitzinger and the Age of ‘Transformation’”, in Ernst Kitzinger and the Making (n. 51), pp. 39–66, sp. pp. 39–49.[↩]

- Thomas Whittemore, The mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul, Paris 1933.[↩]

- Ernst Kitzinger, Early Medieval Art at the British Museum, London 1940.[↩]

- Cyril Pearl, The Dunera Scandal: Deported by Mistake, London/Sidney 1983. On this episode of Kitzinger’s life: Harley-McGowan, “From London to the Antipodes” (n. 54), pp. 49–56.[↩]

- Harley-McGowan, “From London to the Antipodes” (n. 54), pp. 49–50 with further bibliography.[↩]

- Alan Parkinson, “From Marple to Hay and back”, [http://www.marple-uk.com/misc/dunera.pdf, last accessed on October 20, 2022].[↩]

- Harley-McGowan, “From London to the Antipodes” (n. 54), p. 52.[↩]

- Ibidem, pp. 53–4, with further bibliography.[↩]

- James N. Carder, “Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss: A Brief Biography”, in A Home of the Humanities: The Collecting and Patronage of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss, James N. Carder ed., Washington, D.C. 2010, pp. 1–23.[↩]

- Sirarpie Der Nersessian, “Alexander Alexandrovich Vasiliev”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 9/10 (1956), pp. 1–22; Vladimír Vavřínek, “Francis Dvorník – a World-Renowned Byzantinist”, Byzantinoslavica, LXXVI/3 – Supplementum: Homage to Francis Dvorník (2018), pp. 7–20.[↩]

- Petra Moser, Alessandra Voena, Fabian Waldinger, “German Jewish Emigrés and US Invention”, American Economic Review, CIV/10 (2014), pp. 3222–3255; Sascha O. Becker, Sharun Mukand, Volker Lindenthal, Fabian Waldinger, “Persecution and Escape: Professional Networks and Highly-Skilled Emigration from Nazi Germany”, IZA: Institute for Labor Economics (2021).[↩]

- Erwin Panofsky, “Renaissance and Renascences”, The Kenyon Review, VI/2 (1944), pp. 201–36; Kurt Weitzmann, “Probleme der mittelbyzantinischen Renaissance”, Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Archaölogischer Anzeiger, IIL/1–2 (1933), pp. 337–60; Krautheimer, ‘The Carolingian Revival of Early Christian Architecture’, The Art Bulletin, XXIV/1 (1942), pp. 1–38. About the historiographical problem of Renaissance, see, e.g., Jean–Michel Spieser, “La ‘Renaissance macédonienne’: de son invention à sa mise en cause”, in Autour du Premier humanisme byzantin & des Cinq études sur le XIe siècle, quarante ans après Paul Lemerle, Bernard Flusin, Jean-Claude Cheynet eds, Paris 2017, pp. 43–52; Ivan Foletti, Sabina Rosenbergová, “Rome between Lights and Shadows. Reconsidering ‘Renaissances’ and ‘Decadence’ in Early Medieval Rome”, Convivium Supplementum (2021), pp. 17–31.[↩]

- Alan Lester, “Humanism, Race and the Colonial Frontier”, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, XXXVII/1 (2012), pp. 132–48.[↩]

- J. A. Emmens, “Erwin Panofsky as a Humanist”, Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, II/3 (1967–68), pp. 109–13.[↩]

- Erwin Panofsky, “In Defense of the Ivory Tower”, The Centennial Review of Arts & Science, I/2 (1957), pp. 111–22, sp. p. 121.[↩]