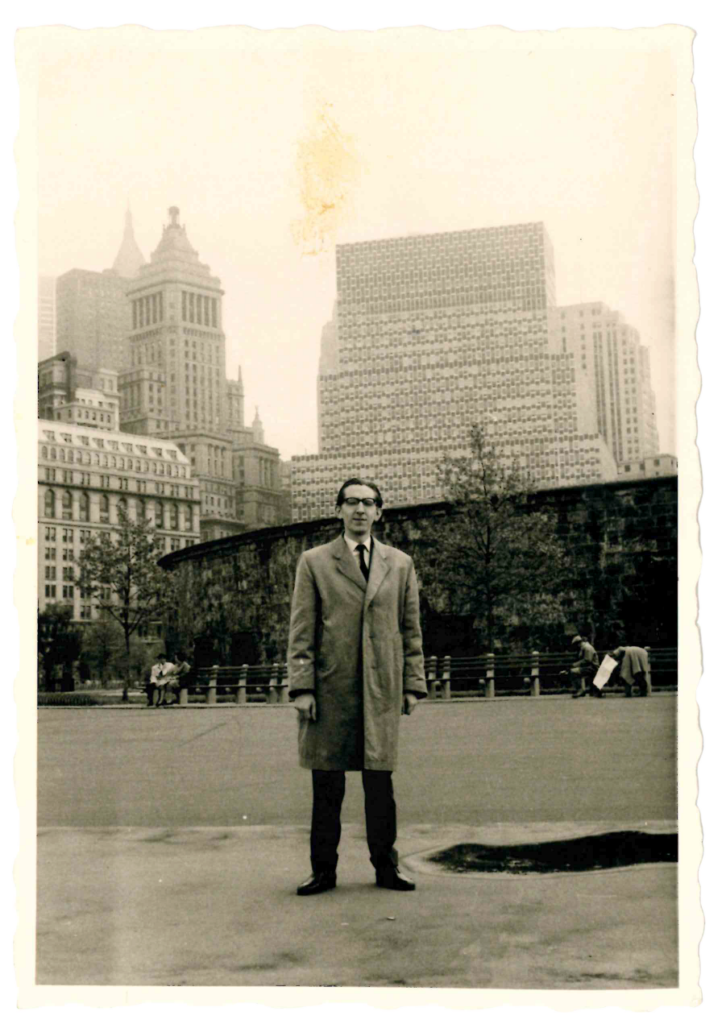

On January 1st and 2nd 2023, I had the pleasure of meeting Hans Belting – who left us on January 10 – for the last time. It was a dense meeting: we concluded a long interview that had lasted since 2017, a discussion that over time became more of a dialogue between friends. Excerpts of this extended interview will soon be published (The Presence of Images. Hans Belting in Dialogue with Ivan Foletti, Rome/Brno, forthcoming). We went through photographs from his youth to more recent years, discussing what art history and Bildwissenschaft were and what they have become. When I left, I was convinced we would have the occasion to meet again. Although we will not, we had the chance to say goodbye, in a way, to each other through this friendship: we discussed images, our shared passion, and remembered the old masters of our discipline. It was the best “goodbye” I could have received.

Hans was a true friend in these last years, and I feel the weight of his absence. What he did, however, for our Department of Art History and for the Center for Early Medieval Studies is even greater: by giving us his library, by becoming one of the editors of Convivium (our shared project with Lausanne and the Czech Academy of Sciences), by attending in this last decade regular scholarly encounters in Brno, he decisively impacted our perception of who we are and our place in the scholarly world. Despite the many other alienating scholars looking to Central Europe from a colonial perspective, he adopted – as maybe always throughout his life – a completely different point of view. In one of the first letters he addressed to me after the publication of the first issue of Convivium, he wrote:

“Now I begin to understand what the whole project is like. It represents an old dream of mine to see a true internationalism between east and west and in a number of possible languages. The prehistory too is so unique, from the time Kondakov lived in Prague”.1

In the name of all the members of our research center, I would like to express first of all our immense gratitude to Hans. Secondly, our deep condolences to Andrea and to all of Hans’ family. Finally, I would like to underline that Hans’ legacy and his presence amongst us is lasting and permanent.

Thus, I would like to open this text with a reflection on the importance of Hans’ scholarship and the ways in which it impacted my own thinking about images. I will take as a reference point one of his most influential books, An Anthropology of Images. Picture, Medium, Body, which I recently had the pleasure and the honor to edit for its Czech translation2.

The Presence of Images

In 2001, one of the books that may have made the biggest impact on the history of art history in the last thirty years was published in German as Bild-Anthropologie: Entwürfe für eine Bildwissenschaft3. Its methodological significance was perceived by its author, Hans Belting, as a definitive step outside the boundaries of the field. In this sense, it is the culmination of a process that began in 1992 when Belting gave up his position as professor of art history in Munich to become a founding member of the Staatliche Hochschule für Gestaltung in Karlsruhe. There he established a new curriculum in art history and media theory and launched an interdisciplinary doctoral program called Bild – Medium – Körper, i.e. Image – Medium – Body. It is no coincidence that it was during his time in Karlsruhe that Belting ceased to think of himself as an art historian, but increasingly presented himself as an anthropologist of the image. He thus continued his efforts to anchor the study of the image in an interdisciplinary manner, which he began as early as 1983 with his legendary book, tellingly entitled Das Ende der Kunstgeschichte?4.

Belting himself considers the Anthropology of the Image as the culmination of an imaginary trilogy devoted to the theory of the image, which he began with his equally fundamental book Bild und Kult: eine Geschichte des Bildes vor dem Zeitalter der Kunst in 19905. As the title suggests, this is the first of a series of steps in Belting’s research that sought to detach the study of the image from traditional art history. The concept of “art” itself did not exist in pre-modern cultures, and so it was necessary to work with and develop an entirely different methodological framework for its study. This was naturally represented for Belting by a history of the image independent of the concept of art. For him, the second part of the aforementioned trilogy is his book Das unsichtbare Meisterwerk: die modernen Mythen der Kunst (1998), addressing the mechanisms through which the image became part of the modern art myth 6. In this sense, then, Anthropology of the Image should be seen as a form completing a process of thinking about and studying images that began in the early 1980s and continued throughout the 1990s. From the point of view of the history of our discipline, this was an absolutely crucial period. With the work of scholars such as Horst Bredekamp (*1947), David Freedberg (*1948), Georges Didi-Huberman (*1953) and Hans Belting, the field of art history was radically transformed. In the same breath, however, I must admit that such a transformation, however fundamental, is in my opinion less enchanting for the reader than the book Bild-Anthropologie itself. Despite being already more than twenty years old, the text has not aged at all. What is more, the questions Belting asks are, from my point of view, particularly relevant here and now.

The History of the Image and the Mortal Body

Bild-Anthropologie can be divided into two main parts. The first is devoted to a comprehensive definition of the anthropology of the image itself, and it must be admitted that this is a demanding text to read. The individual concepts are presented in a truly dense form, but in many ways they are revolutionary. Belting draws heavily on other disciplines – in addition to the obligatory anthropology and religious studies, he especially incorporated the history and theory of cinema and photography – to guide the reader to a fundamental definition of what an image is and how to define it in relation to the human body and mind. Belting presents images in the broadest possible perspective, as entities that materialize in the mind of the viewer: “Internal and external images”, Belting writes, “fall indiscriminately under the term ‘image’. It is clear, however, that the medium is to images what writing is to language”. Thus, he implicitly draws on the Orthodox tradition of the canonized texts of John of Damascus (after 650–750) and the canons of the Second Council of Nicaea (787), where this broad semantic spanning the term “image” is explicitly thematized. In this approach, wherein the image is something immaterial, cinematography and, at the turn of the millennium, virtual space play key roles. This conception lead Belting to define a triad that makes the existence of the image possible: the “image” as a concept, the “medium” as a carrier, and the “body” as the place where images are realized. Simply put, the image is realized in the mind through a specific material or immaterial “medium”, such as an oil painting, a bronze sculpture, or even a virtual display. Belting thus points to a certain emancipation of the image from the traditional categories of fine arts, and at the same time to the quite fundamental role of the body and mind in the whole process of its creation and existence. Compared to traditional art history, which often concentrates on the “medium”, whether it is considered “art” or not, this is a real breakthrough.

In the second part of the book, much more rewarding for the reader, Belting engages in a breathtaking race against time and, I might add, against the concept of death. Indeed, after a chapter devoted to the modern dichotomy between portrait and emblem as two fundamentally different media for image-making (in the mind), the author embarks on a journey through time and space to some of the earliest known representations. Thus, we find ourselves in Jericho, seven thousand years before Christ, where we encounter sculptures fabricated from lime-base plaster and clay, created directly on the skulls of the deceased. These, in Belting’s words, “have lost their face in decay, [which] is reconstructed by the sculpted and painted face”. The aim of the whole operation, he said, was to “‘retain’ the face that the deceased would otherwise have lost”. The sculptures are thus created as a response to death, which they attempt to stop or reverse. Belting’s analysis passes through prehistoric cultures, ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, to return in an arc to the invention of photography and the development of the medium. The connecting line throughout this section is – in a truly longue durée timeframe – the relationship between the image and death. From Egyptian statues, which in the contemporary imagination were meant to be brought to life by breathing in the soul, to masks and Greco-Roman monuments, Belting tells the story of death and the human attempt to cope with death through images. This second part could certainly be faulted for a certain simplification, as thousands of years of human culture are presented here in just a few dozen pages. But the story that stands out precisely because of this “simplification” is a gripping one, which imaginatively restores the magnitude and gravity of death, marginalized in “Western” society in recent decades, to its rightful place in human history.

The anthropology of the image thus fundamentally marks the history of art and places it in the broader framework of the history of the image. Even further, its author was not afraid to apply this paradigm to the question of the history of memory as well.

Anthropology of the Image Today

The importance of Belting’s text, however, lies not only in his ability to question, as in the above example, the role of death in contemporary civilization. The theme that personally struck me most, almost twenty years after first reading it, is certainly the way Belting sees and describes the fundamental social changes that virtual images bring to our world. In 2001, he seems to have predicted the development and impact of modern technology on our everyday lives. Belting’s analysis first and foremost describes a now ubiquitous phenomenon:

“Today […] we are fascinated less by bridges across time than by the crossing of space, as for example by television images that transport us to another place ‘out there’. TV bridges an absence in space, not in time. In the process we exchange the place where we are for the place we are looking at” 7.

This is a very apt description of the reality we encounter every day. Through images, or rather through computer and smartphone screens, people mentally leave – for shorter or longer moments – the space where their bodies are. This creates an entirely new social situation where bodies (for example, of lovers in love in a restaurant) sit together, absent in mind. Through the images/screens their psyche lives in other, more or less distant realities with more or less concrete people. This state of affairs literally replicates Belting’s words when he argues that “The ‘here and now’ is changed into a ‘there and now’, where we can, we think, be present without our bodies”8. Twenty years ago, he captured and described the mechanism that is responsible now for fundamentally transforming social habits, attachments, and skills. Social networks and the electronic images that can be created by and for them undeniably play a central role in this state of absent presence. Belting anticipates and explains this phenomenon too, at a time when social networks were but the faint music of a distant future:

“Pictures – including digital media, and in fact all media before or after – can alter the perception of our bodies, representing us as we wish we would be. They can, for example, turn artificial bodies that cannot die” 9.

The ideal images we see daily on social media, these “elektronische Spiegel”, must therefore be seen in continuity with past desires. Through the obsessively produced and not infrequently enhanced images of ourselves, we long to overcome time and the unspoken fear of death; of the moment when, according to Belting, the body turns into an image. At the same time, the myth of Narcissus falling in love with his own image comes to life in Belting’s words. In this context, it is also possible to understand another throughline of inquiry in Belting’s text. It is the question of the mask in pre-modern societies, which the author projects into the virtual world. According to him,

“The ‘Net’ opens up realms of fantasy and an unbounded freedom of communication, in which users can feel newborn. They put on ‘digital masks’ or ‘ersatz faces’ behind which they pretend to change their identity” 10.

The anthropology of the image thus offers the reader the tools to understand current social phenomena in the context of a much broader and highly consistent theory. Virtual profiles, where their owners modify or even fundamentally change their (not only) visual identity, can thus be seen within the broad narrative of the mask. From our perspective, however, it is also crucial that Belting has almost prophetically predicted the mechanisms behind the societal phenomena that move the present, and which were still difficult to foresee, let alone to such an extent, at the beginning of the millennium. In my opinion, this only confirms the validity of his methodological approach.

An equally prophetic quote from the book, in which the author talks about the power of virtual images, states:

“It would appear that in the conflict between body and medium, digital hypermedia have won. Does this mean that the traditional history of the image – indeed, every history of the image – has come to an end? Are we left with nothing to study but the archeology of historical pictorial media?”11

Such reflection could be perceived pessimistically, with its touch of attachment to the past. In its extreme form, it seems Belting gives the digital images of the present the power, with a bit of hyperbole, to “swallow up” the entire pictorial world, a bit like the Nothingness that tries to swallow up the realm of Fantasy in The Neverending Story. Belting, however, had assured the reader otherwise, saying that

“images resemble nomads. They migrate across the boundaries that separate one culture from another, taking up residence in the media of one historical place and time and then moving on to the next, like desert wanderers setting up temporary camps” 12.

For Belting, then, the phenomenon of the image is not only incredibly topical, but also persists through all stages of human existence, with which it is intrinsically and inherently linked.

From the perspective of the present, another part of Belting’s reflection, which discusses the role of the image as a mediator of dominant social and cultural power, seems pressing:

“The history of their [the Spaniards] colonization can be viewed as a tantamount ‘war of images’, to quote the title of a book by Serge Gruzinski […] Any encounter with another culture raises identity issues of the sort that are apt to arouse protective feelings. The conception of what constitutes an ‘image’ is one such issue. It is tempting to simply exclude the images of ‘the Others’ from recognition as alternatives in their own right” 13.

This idea can also be applied to contemporary visual culture: just recall the recent image rhetoric of the so-called Islamic State. Incredibly brutal and cruel to the eyes of any outsider, the images chosen by this institution had a threefold function: to define its own aniconic identity, to destroy the images of “the other” – namely the monuments in Palmyra – and finally to use the visual language of its enemies (i.e. videos typical of Western culture) to systematically intimidate them by sadistically distorting their own visual culture. Image, in this case, functioned as a cultural violence. With a tiny, dominant minority generating this visual language, this manifested a peculiarly dense image politics which excluded the vast majority of image production from the “image proper” to the Islamic State. In a sense, identity is collected around and through images and image relations. In Belting we find further tools for perceiving current events – the role of the image as mediator throughout the coronavirus crisis or within the Russian aggression in Ukraine. On the one hand, the author explains how tools of information dissemination have shaken collective trust in images:

“The mass media have done their part in shattering the ‘trust in the image’ and replacing it with a fascination for media staging that openly displays its effects and produces its own image reality” 14.

In a situation like this, where images act for and on the part of dominant powers, where images come with hidden motivations and mirages, any image can be challenged. Public trust is a priori threatened, while distrust becomes a fundamental social feature. The paradox, however, is that at the same time, images in the mass media are given “more authority than our own experience of the world” 15. Thus, perhaps every Italian citizen interviewed about the first wave of coronavirus in the spring of 2020 will talk about the convoy of military cars that transported coffins along the motorway in pandemic-ridden Lombardy. It is a purposeful image, spread from the national television station Rai through other mass media to the general population. The gravity and power of this selective image was so strong

These few thoughts confirm the extent to which the research and thinking of Belting were truly visionary: twenty years after its first publication, this book is still urgently relevant, something that can be said of only a truly limited number of scholarly publications.

In death, Hans Belting’s presence has become an image, but the mental images he has produced through his writing and through personal encounters are more vibrantly alive today than ever.

- Except few citations which were not included in the English translation, and which are translated from the original German text by Adrien Palladino, all English citations are taken from Hans Belting, An Anthropology of Images. Picture, Medium, Body, translated by Thomas Dunlap, Princeton/Oxford 2011.[↩]

- Hans Belting, Antropologie obrazu: návrhy vědy o obrazu, translated by Iva Kratochvílová, introduction by Ivan Foletti, Brno 2021.[↩]

- Hans Belting, Bild-Anthropologie: Entwürfe für eine Bildwissenschaft, Munich 2001.[↩]

- Hans Belting, Das Ende der Kunstgeschichte?, Munich, 1983.[↩]

- Hans Belting, Bild und Kult: eine Geschichte des Bildes vor dem Zeitalter der Kunst, Munich 1990.[↩]

- Hans Belting, Das unsichtbare Meisterwerk: die modernen Mythen der Kunst, Munich, 1998.[↩]

- Belting, Anthropology of Images (n. 1), p. 20.[↩]

- Belting, Anthropology of Images (n. 1), p. 20.[↩]

- Belting, Anthropology of Images (n. 1), p. 17.[↩]

- Belting, Anthropology of Images (n. 1), pp. 59–60.[↩]

- Belting, Anthropology of Images (n. 1), p. 25[↩]

- Belting, Anthropology of Images (n. 1), p. 21[↩]

- Belting, Anthropology of Images (n. 1), pp. 34, 35–36.[↩]

- Belting, Bild-Anthropologie (n. 3), p. 41.[↩]

- Belting, Bild-Anthropologie (n. 3), p. 28.[↩]